Chapter 5: Authority and Bias

5.5 More moves for evaluating scholarly sources

Evaluating scholarly information takes more than just verifying that it has been peer-reviewed. You also need to determine if your source is accurate, reliable, and relevant. In addition to using SIFT, there are some other strategies and considerations that can be useful for quickly assessing a scholarly source.

In this section, we’re going to focus on articles. However, you can also use these strategies when evaluating other types of scholarly sources, such as books. Although the sections of books and articles are labeled differently, they generally serve the same purpose. These sections can provide information and structure to help you quickly evaluate the source. For example, the summary section at the beginning of an article or book chapter is called the abstract, but in a book, this is called the introduction. However they’re labeled, you can use the information found within them to evaluate the source.

Skim the abstract and conclusion

If an article has an abstract, read that first. This summary gives you a general idea of what the authors were trying to accomplish, as well as a brief description of their experiment, observations, or analysis. If the abstract is too complex or technical, that is an indication for what the rest of the article will be like. If you can understand most of the language used in the abstract, highlight terms that you don’t recognize to look up later. This can be a useful learning experience. However, if you can’t understand the article at all, then it may not be the right resource for you, even if it’s written by the foremost expert in the field.

Once you’ve read the abstract, you can skip down to the conclusion. With scholarly articles, you don’t always have to read straight through from start to finish. Strategically skipping around and skimming specific sections can help you understand the big takeaways from the research. The conclusion usually includes information about major findings and why the author thinks they’re important. By reading the conclusion, you can verify that the impression you got from the abstract is correct and check that the article is actually relevant for your research question. This can also inform how you read and interpret the rest of the article.

Explore the rest of the article

If you found the abstract and conclusion relevant for your research topic, read the rest of the article. This will give you the details you will want to use and cite in your project.

Dig into the methods section to understand how the author(s) conducted their research, including how they gathered their data (e.g. surveys, interviews, experiments, or observations) and why they chose that method. Be on alert for approaches that are too general or don’t give any detail, such as only stating “We ran a qualitative analysis.” If you don’t understand a term or phrase, take note of it to look it up later. Reviewing a paper’s methods can give you a deeper understanding of how the authors got their results and will put their findings into a better context.

The results section (sometimes called discussion) provides more specific details about what the authors found. This includes descriptions of overall results and their corresponding data. Important or notable findings may be pulled out in tables, figures, and graphics, to help you understand the data more quickly or completely. Reading the results section will give you the full breadth of the research findings, not just the highlights you saw in the conclusion.

Did you know?

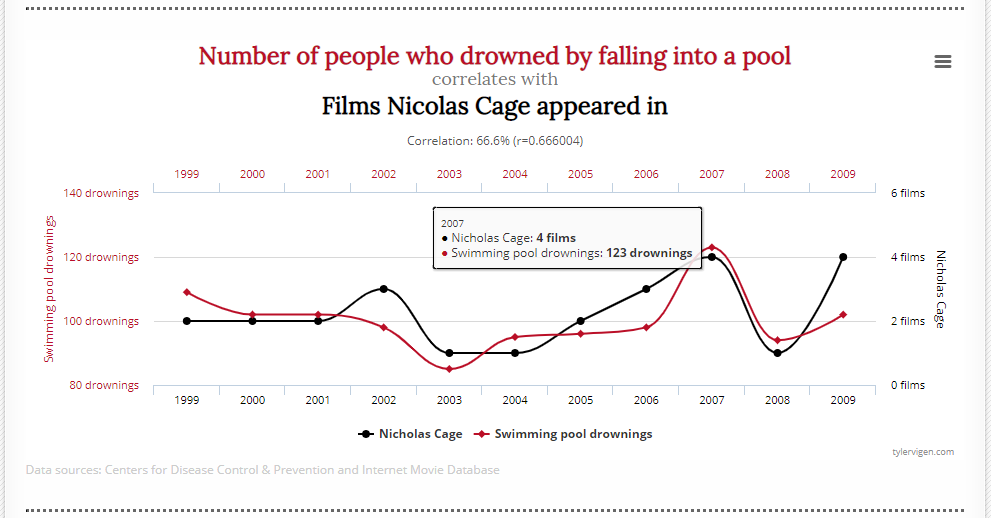

Correlation does not equal causation! Claims presented in a paper can be misleading even when they appear convincing. Trends in data can seem to form patterns or overlap (correlation) without actually being related in any way. Good research investigates whether there is truly a connection where one change causes another (causation).

Is Nicolas Cage’s presence in movies really impacting the number of swimming pool drownings? Is the number of pool drownings impacting the number of Nicolas Cage movies made per year? No! These two variables were chosen because they line up, not because there is actually any connection between them. You may notice this problem more often in news media, which is why it’s important to go back to the article (i.e., Trace it back) to find what the research actually says. Remember this when you’re looking at scholarly graphics, as well, though they may not be nearly as entertaining.

Other things to consider

As you review the paper, notice whether and how the author uses citations. Is the author supporting their research with citations to other papers? If the article you are reading makes broad statements like “studies find that students love LIB 160,” make sure there is at least one study cited at the end of that sentence. If there are citations, make sure they are not leading to only the author’s own papers. This is an example of self-citations and may be a sign that the author is only focusing on their own findings, and disregarding the work of other researchers.

Finally, consider when your source was published. This date can affect how useful (or not) that source will be for you now. Depending on your topic or assignment, you may need something published within the last five or ten years. This can be the case when researching recent events or technological innovations. For other topics, it may be necessary to consult an older source, such as for research on a historical event or a longstanding theory in your discipline. Keep in mind, if a theory has been around for a long time, it has had more opportunity to be criticized, overturned, built upon, or reinforced. You may need to seek out newer sources about the same topic to figure out whether the information in your original source is outdated today. If you’re not sure whether a source’s publication date matters for your project, ask your instructor.