Chapter 4: Fact Checking & Misinformation

4.4 Investigate the source

Once you are sure that you are on task with your research, you can move on to critically evaluate your sources. Even if the sources you’ve found seem to fit your project’s topic well, you will still need to evaluate their quality and context in other ways. Here are some points to consider:

- Reputation/Authority

- Purpose

- Bias

You’ll need to understand your sources and decide whether each is worth using. If a source you encounter is low quality or if you can’t verify that it’s reliable, your best strategy is to not use it and move on to other sources.

Don’t rely on first impressions to tell you whether a source is good. There are many great academic websites that appear outdated or poorly designed because the creators’ expertise lies in content rather than web design. You might have noticed that not all of your NKU professors are great at using Canvas, for example. Your NKU course pages may not be the most attractive, but because your professors are experts in their course topics, you can feel confident in using their content. In contrast, some intentionally misleading websites appear sleek and well-supported because their creators have heavily invested in making their work look “reputable.” Rather than evaluating a website based solely on the way it presents itself, follow these steps:

Explore the reputation of the author

Investigate how other sources talk about the author or publication (newspaper, journal, etc.) to learn more about your source’s reputation and authority. Authority is another way of saying “expertise” or “qualifications.” Understanding an author’s background can help you decide whether to trust what they have produced. An author has developed authority in a subject when they have extensively studied or worked in that area.

To check if an author is an authority on their topic, search for them on Google or Wikipedia to determine whether they have a degree or job related to the topic they are writing about. For journalists, check whether the author usually writes about research or if they work primarily on editorial and opinion pieces. Background checks like this may also yield information about an author’s reputation in the academic or professional community. LinkedIn is also good place to find background information on an author. You can find out about their education, where they have worked and how long, and their interests. If the author of one of your sources has experience working with specific organizations or universities, check the organizations’ websites for further information. Many scholarly organizations provide information about their staff on their websites. For example, NKU provides a full list of its instructors categorized by department.

If an author lacks experience in your research topic or has a bad reputation, find a different source. Luckily as an NKU student you have access to many different academic sources via Steely Library.

Investigate the reputation of the publication

In addition, you can assess your source’s authority by investigating the reputation of the publication that produced it. For an article, you can check how the journal, newspaper, or magazine is described and perceived by experts in its field. For books and book chapters, you can check the reputation of the publishing company. You can use Wikipedia and Google to find out more about publications or publishers, just like you can with authors. For example, if the Wikipedia entry for a journal describes it as “infamously racist,” you might want to find sources for your paper elsewhere. Here’s a tip: when using Google to search for this kind of information, include “reputation” as a keyword to find how the publication is perceived, and not just links to its website.

This video from Mike Caulfield walks you through the process of searching for a publication’s information online:

You may have noticed by now that we’ve mentioned Wikipedia a few times. Yes! Just like we said earlier in this textbook, Wikipedia can be incredibly useful for finding background information about an author or publication. You may find more works by the author you are looking into, as well as more articles about them in the reference section of a Wikipedia entry. Keep in mind that Wikipedia does not cover all topics with the same level of detail. An author can still be an expert in their field even if there is no Wikipedia entry for them. Also, since Wikipedia can be edited by anyone, always double check any information you may find on it.

Examine your source’s purpose

A publication’s purpose might be to inform, convince, entertain, sell products, or promote a particular viewpoint. As you investigate your source, you may come across this information through purpose statements. A company or organization’s purpose statement does not necessarily represent its true agenda, but it can give you a good idea of how they want to be perceived. A few examples of purpose statements are provided below:

- TikTok: “TikTok is the leading destination for short-form mobile video. Our mission is to inspire creativity and bring joy.”[1]

- Goop: “We operate from a place of curiosity and nonjudgment [sic], and we start hard conversations, crack open taboos, and look for connection and resonance everywhere we can find it.”[2]

- JSTOR: “We help you explore a wide range of scholarly content through a powerful research and teaching platform.”[3]

Just as you should search for context outside a source to learn about its reputation, don’t stay within the website you’re exploring when you’re trying to figure out its purpose. Find out what other sources say about the company or publication’s purpose as well. For example, checking Wikipedia about Goop finds this: “Goop has faced criticism for marketing products and treatments that are based on pseudoscience, lack efficacy, and are recognized by the medical establishment as harmful or misleading.”[4]

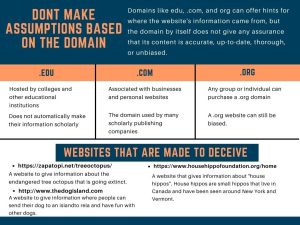

Don’t make assumptions based on the domain

Domains like .edu, .com, and .org can offer hints for where a website’s information came from, but the domain by itself does not give any assurance that its content is accurate, up-to-date, thorough, or unbiased.

- .edu websites are hosted by colleges and other educational institutions, but that doesn’t automatically make their information scholarly. For example, personal home pages for students and staff may have a .edu domain if they’re hosted by the university.

- .com is often associated with businesses and personal websites, but it is also the domain used by many scholarly publishing companies. Journals hosted on .com websites aren’t necessarily any better or worse than journals hosted on .edu or .org websites.

- .org websites are often assumed to represent non-profit organizations, but any group or individual can purchase a .org domain. Even if a .org website is for a non-profit organization, it can still be biased. Non-profit organizations are not necessarily objective and neutral, and their biases may be reflected in how they present their interests and related research. Examples of this include the ways some political organizations, animal rights activist groups, or other organizations use marketing tactics to influence the way you feel about their issues, as opposed to using objective research.

Recognizing AI Generated Content

Recent advancements in machine-learning have brought us the ability to generate text and images through generative AI systems. These systems are based upon pre-existing AI systems that were used to analyze data sets, but these generative systems are programmed to create new content based on a given data set. Despite their rapid improvement, content generated by AI is considered untrustworthy and should not be used as a source for information.

Generative AI creates content by analyzing and mimicking whatever content it is supplied with in its code. This means that generative AI can easily inherit bias and is not capable of discerning whether the claims it makes are accurate. As these systems continue to be developed, it becomes more and more difficult to distinguish AI generated works from those of real people. Fortunately, there are still methods of finding out if what you’re looking at is AI generated.

For AI generated images…

- Consider the context of the image. Is it supposed to be a depiction of real life, or an illustration? What interpretation are you meant to draw? Does it make sense?

- If possible, find the image in a higher resolution and zoom in. This will make it easier to spot inconsistencies or unclear borders between objects and backgrounds.

- Look for asymmetry and physical inconsistencies. This alone will not be effective on high quality images, as the systems that create them are learning to avoid these mistakes.

- Look for strange, glossy, or airbrushed textures. AI systems often struggle to replicate textures and lighting appropriately.

- Perform a reverse image search. Find out if the image has appeared anywhere else and, if so, how it was used there.

For AI generated text…

- Look for typos

- Look for info that is incorrect or outdated. Cross reference with a different source and see if the facts are consistent.

- Pay attention to the tone. AI generated text may have a blunt, emotionless tone. You might say they sound robotic.

- Note repetitive speech. Are there any words or phrases that show up unexpectedly often?

With both text and images, it is recommended that you check the source of the content and who is distributing it. You should consider if the source has a reputation for using AI generated content and look for any admittance that the work is AI generated. Keep in mind, though, that not all sources will disclose their use of AI.

- TikTok. (n.d.). Our mission. https://www.tiktok.com/about ↵

- Goop. (n.d.) What's Goop? https://goop.com/whats-goop/ ↵

- JSTOR. (n.d.). About JSTOR. https://about.jstor.org/ ↵

- Wikimedia contributors. (n.d.). Goop (company). Retrieved August 12, 2021 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Goop_(company) ↵