Structure the Argument

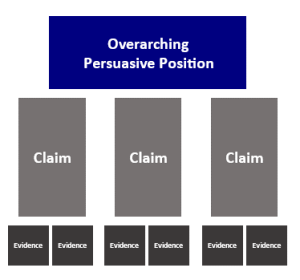

Now that you have set the top-level strategy for your persuasive appeal, you can turn your attention to developing the structure for your persuasive argument. The basic structure of an argument is to have an overarching persuasive position (which you already established), which is supported by persuasive claims, which in turn are supported by evidence. You can see this illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 2. Visual representation of persuasive argument structure. |

Here are some guidelines for building a persuasive structure for your own messages.

Build Your Supporting Claim Framework

With your overarching persuasive position in place, your next task is to identify the claims that are needed to support your position. You can think of your supporting claims as pillars that hold up the probable truth of your argument. Building a supporting claim framework consists of identifying necessary claims and then ordering them.

Understand Types of Claims

A good starting point to identify specific claims for your argument is to understand the types of claims that you can make. Recall that claims are debatable statements that you attempt to make other people accept or understand. There are several types of claims you can choose from to support your persuasive position.

Comparative Claims

A comparative claim is a claim that one alternative is better than (or worse than) other options. This kind of claim is useful if you want to influence your receiver about the relative ranking of competing options. Comparative claims are usually worded in ways that directly assess the options against one another and may contain words like better/worse, more/less, or any word in the superlative form (words ending in -est).

Example: Sara Pandey is the strongest candidate for the job.

Example: Of the three new project options, Option B is the riskiest.

Causal Claims

A causal claim is a claim that one phenomenon causes another phenomenon to occur or change. This kind of claim is useful if you want to persuade someone that a particular issue is the source of a problem or, perhaps alternatively, if it is the source of the solution. Causal claims can be made about things that happened in the past, things that are currently happening, or even things that may happen in the future (which is a lot like a predictive claim).

Example: Our recent jump in sales can be attributed to the effectiveness of our recent training initiative.

Example: Our turnover rate is high because we don’t pay as well as our competitors.

Predictive Claims

A predictive claim is a claim about something happening a certain way in the future. This kind of claim is used to persuade your receiver about the likelihood of a particular outcome. Predictive claims can be made about trends and trajectories (this trajectory will reverse by the end of the year), projections or promises of future performance or behavior (we will complete this step by the end of the quarter), or even demonstrate future causal relationships (if we implement this program, we will have this outcome).

Example: Implementing this new recognition program will improve employee morale.

Example: Our start-up company will be successful.

Value Claims

A value claim is a claim about the subjective value of things. This kind of claim is used to influence beliefs and attitudes toward a phenomenon of interest. Value claims can be made about an object’s worthiness, fairness, righteousness, desirability, attractiveness, or any other descriptor that can’t be directly measured. Value claims can be made about something just by itself (this project is the morally right thing to do), or they can be made by comparison (innovation is more important than predictability).

Example: The proposed remote work policy is unfair.

Example: Although this initiative is expensive, it will be worth it to take care of employees.

Evaluative Claims

An evaluative claim is a claim about how something is rated or judged against a standard. This kind of claim is used to persuade your receiver about how well (or how poorly) someone or something compares to expectations. Evaluative claims can be similar to value claims in that sometimes, you may evaluate against a subjective standard. Still, the difference is that with an evaluative claim, the focus is on judging something against a standard. For example, you may use evaluative claims to describe job performance, assess progress toward a goal, or evaluate a completed job.

Example: Maria exceeded expectations for a first-year associate.

Example: Our company is not living up to its commitment to being a responsible steward of the environment.

Identify Necessary Claims

Knowing some of the basic claim types available, you can now identify the claims that you will use to support your argument. This task requires critical thinking skills to identify all the key claims that will be needed to support your overall arching position.

Factors such as the complexity of your topic, the size and significance of your request, and the favorability of your receiver will affect how many supporting claims you need. Frequently, persuasive arguments are supported by three claims. But that is not a hard-and-fast rule. There may be times when a single supporting claim will be all that is needed and other times when you will need many more. Your job is to include as many claims as are needed to provide sufficient support for your argument.

Example: Making a recommendation to update the office workspace:

-

- Teamwork is at an all-time low. [evaluative claim]

- A primary cause of our teamwork problems is our current workspace. [causal claim]

- Redesigning our workspace will enable better teamwork. [predictive claim]

Example: Writing a letter recommending an employee for a promotion:

-

- Isiah is a hard worker. [evaluative claim]

- Isiah is intelligent. [evaluative claim]

- Isiah is ready for the next level of responsibility. [evaluative claim]

- Isiah is the best candidate for this role. [comparative claim]

Order the Claims

With your claims decided, it is time to order them for maximum impact. There are no specific rules that have to be followed. So, the decision is ultimately up to you. But here are two different approaches that could help you decide.

One approach is to order the claims using a logical pattern. Chapter 3 has several suggestions for logical ordering. You can select one of those patterns as you write your claims. For example, you may have to identify a problem before you can present the solution. Or you may have to work in a start-to-finish chronological pattern. Alternatively, you can write your claims first, read them in different orders, and then choose the one that flows the best.

Sometimes, your claims won’t force you into a particular logical order. For instance, in the example provided previously about writing a recommendation letter, the four points could be written in any order and still make perfect sense. When that is the case, you will have a better chance of being successful when you put your most important or compelling points first. The first point made is usually more memorable, and the sooner you can move your receiver to a favorable position, the more likely you will be to meet your persuasive goals.

Communication Tip: From Topics to Claims

When it is time to persuade someone, one of the simplest strategies you can use is to make sure you explicitly state every claim. This may sound obvious, but in practice, people have a tendency to skip over their claims and either announce their general topic or state their evidence.

Below is an example of how a topic can be transformed into a claim through several steps. As you read each one, pause for a moment and consider how much the claim would persuade you if you were the receiver of this message.

| Step | Example |

| 1. Identify the topic | Isiah’s experience |

| 2. State it in a declarative sentence | Below, I summarize Isiah’s experience. |

| 3. Take a position | Isiah has accumulated a wide range of experience. |

| 4. Link it to the overall position | Isiah’s wide range of experience is a good match for your position. |

Support Each Claim with Evidence

You’ve already learned a lot about how to be evidence-driven in the previous chapter. In addition to those principles, here is more advice about how to apply your evidence-driven competency to persuasive situations.

Be Complete

One of the questions you may be asking yourself is, “How much evidence do I need?” Unlike school assignments, where you may have been given a specific number of sources to cite, in business, there will not be specific instructions. Instead, you will have to use your judgment to determine if your argument is sufficiently supported.

To make the determination, you should remember the following.

First, claims are inherently debatable statements. So, you must start from the standpoint that your receiver will not automatically believe every claim you make. Therefore, each claim you make should have at least one piece of supporting evidence to support its probable truth.

Second, some claims will be more contentious than others. Claims that you identify as higher-stakes or more debatable will likely need stronger evidence. That could come from using higher-quality evidence, simply using more evidence, or some combination of quality and quantity.

Third, remember that persuading someone requires you to be receiver-centric. That means you should put yourself in the position of your receiver and ask yourself, “Knowing what I know about my receiver, would he or she believe this claim given this evidence?” If you aren’t sure that the answer is yes, you may need to find more evidence.

Be Selective

Sometimes, the problem isn’t having insufficient evidence; there may be times when you find you have an abundance of evidence. While it may be tempting to pack as much evidence as you can into your message, that is usually not the most persuasive option. Too much evidence runs the risk of overwhelming your receiver, making them less likely to read your message. A better strategy is to select the one or two most compelling pieces of evidence.

Your Turn: Building Your Argument

Go back to the previous scenario, where you intend to propose an employee development program for your company.

Fill out the Supporting Argument Grid below by answering each of the following questions.

- What are your three main claims? Try to write each one as suggested in the Communication Tip box.

- Can you label each claim with what type of claim it is?

- What kinds of evidence could you use to support each claim? Which claims would need the most evidence?

| Claim 1 | Claim 2 | Claim 3 | |

| Claim |

|

||

| Type | |||

| Evidence |

|