Strategically Select Content

As you strive to make your messages more concise, the biggest impact you can have is strategically selecting content. To be strategic, you must make determinations about content with both your goals and your receivers in mind. At all times, you need to ask yourself two questions: “Does this message give my receivers all the information they need to act on my message?” and “Does this message contain any extraneous information they don’t need?”

A recent sales meeting we attended illustrates a poor balance between those questions. We had scheduled a 45-minute meeting between key decision-makers and a technology supply company. When the sales presentation began, the speaker spent much of the time providing an overview of four distinct product lines one by one. He shared minute details about the products (like what colors they came in) and told us stories about different organizations that use their products. Then, with less than 15 minutes remaining, he started telling us about the fourth product line—the one that is specifically designed for higher education applications and the only one we were interested in.

But by then, he had run out of time and used up all our patience. He couldn’t introduce us to all the higher education products we may have wanted to purchase. He couldn’t inquire about our needs and direct us to targeted solutions. He couldn’t describe how his products were better than those of his competitors. Had he strategically cut out the information we didn’t need, he would have had ample time to cover the information we did need to act on the message. In short, instead of making a sale, he made a bad impression.

So, don’t follow this ineffective salesperson’s lead. Instead, follow these strategies to craft concise messages that enable you to achieve your communication goals.

Include Information Your Receiver Needs

In order to write a complete message, you must ensure your receivers have all of the information they need to respond to your message or take action. Understanding your receivers and how they will use your message is essential to deciding the right kind and amount of information to include.

Even on the same basic topic, different receivers have different needs for information. For instance, assume that you are announcing the launch of a new app. Top-level leaders in the company might need information to persuade investors to make a bigger investment. In that case, you should provide information on what the app is, when it will launch, and how it’s projected to impact sales. The sales team might need the information to sell the product to customers. So, you should emphasize the app features and how they differ from competitors’ apps or other apps you built in the past. You might need specific details from your development team to ensure that the launch will go off without a hitch. Your message to them may include more questions than answers: Are all the bugs fixed? Are all our ads ready to go? Are there any last-minute problems that need to be addressed?

In addition to your immediate goals, also remember to consider any future use that your receiver may have for your message. Whereas many messages will never be referred to again, others may be accessed at some point in the future. If your message is recording important decisions, sequences of events, or other activities, make sure to include details your receiver will need to know in the future. Refer to the section in Chapter 3 on “stand-alone sense” for help.

Finally, test your message for completeness. For shorter messages (or those messages with lower stakes), you can simply review the message yourself. Put yourself in the position of your receiver, critically read through your message, and look for any missing pieces of information. Or you might look for specific answers to the “5 Ws and H”: Who, What, Where, When, Why, and How. For longer or higher-stakes messages, consider asking someone else to review the message for completeness. Being less familiar with a message helps people spot missing information more easily.

Cut Information Your Receiver Doesn’t Need

To write a concise message, you must eliminate any information your receiver doesn’t need. This is the step where you can make the biggest difference in terms of crafting briefer messages. Ideally, you’d plan ahead and wouldn’t write anything unnecessary in the first place. But oftentimes, you’ll find that you’ve ultimately included something extraneous. That’s when you’ll have the tough job of deleting it, no matter how long it took you to draft it.

There are several typical culprits of extraneous information: information that is relevant to you but not your receiver; too much detail when only the big picture is needed; multiple facets of a topic when the receiver is interested in only one facet; and topics that are only tangentially related (or, even worse, not related at all). Here are some places where you can cut extraneous information.

Cut Information That Is Irrelevant to Your Receiver

Just because information is highly relevant to one individual doesn’t mean that it is relevant to your receiver. You must ask yourself, Does my receiver care? And if the answer is no, then cut the information.

Consider the case of a job candidate who needs to submit an expense report to cover incidental expenses that the company promised to reimburse. The administrative specialist who is handling the reimbursement cares about internal processes, policies, and specific computer systems. The candidate cares about the steps that need to be completed to file an expense report.

Extraneous Content: After I get your receipts, I will create a profile for you in our new Rapid Reimbursement™ computer system, which we implemented only three months ago. Then, I will enter your receipts and categorize each expense. At that point, I will submit a workflow request that routes the report to Mr. Xie, the manager who interviewed you, and then Ms. D’Angelo, the Accounting Manager, who is responsible for approving all reimbursement requests. Once all approvals are in, it will take 3–5 business days for a check to be cut and mailed to you.

Concise: As soon as I get your receipts, I will process your expense reimbursement immediately. We will mail a check to you within 7 business days.

Delete Warm-Up Information

Sometimes, you might struggle with how to start a message, especially if it is a high-stakes message. If you don’t have exactly the right words—and sometimes if you don’t know the answer—you may start by freewriting the ideas on your mind. While this can be an effective strategy to get started writing, it rarely adds anything the receiver needs to act on the message. So, just remember to delete that freewriting “warm-up information” before you send the message.

Extraneous Content: You had asked that we all respond to this message with an idea for making the department greener. I thought about it for a long time and considered several options. Some of the ideas seemed really good at first but weren’t very feasible. After much deliberation, I finally decided to recommend putting mixed-stream recycling bins on every floor.

Concise: My idea for making the department greener is putting mixed-stream recycling bins on every floor.

Remove Think-Out-Loud Information

There will be times when you are writing when you will think not only about how to write something but also about what you are writing. Maybe you are thinking about changing your position (Is this the best use of our limited funds?). Maybe you need to gather better support (I wonder if there is a more current market report available). Maybe you need to confirm facts before communicating them (I should double-check with our contractor on the timeline).

When this happens, you may be tempted to put these “think-out-loud” questions or ideas into your messages. Sometimes, there might be good reasons to do so, such as if you want to seek input from your receiver. But if you can get answers to your questions and then revise your message to incorporate those answers before sending it, you are bound to write far more concisely.

Extraneous Content: [Message 1, before calling Amelia] We will meet on Tuesday at 11 a.m., assuming Amelia Hamilton from HR can attend then. If she can’t, our alternative times are Tuesday at 2 p.m. and Wednesday at 9 a.m. I will call Jenny to confirm the day and time. In the meantime, please review the candidates’ materials and rank your top three.

Less Extraneous Content: [Message 2, after calling Amelia] I have now heard back from Amelia Hamilton in HR. The only time she had available was Wednesday at 9 a.m. We will meet then.

Concise: Our next meeting will be Wednesday at 9:00 a.m. Amelia Hamilton from HR will join us. Please review the candidates’ materials and rank your top three.

Replace Detail with a Summary

Having too much detail can make your messages unnecessarily long. To make your message more concise, ask yourself how much detail your receiver needs. If your receiver only needs the big picture, then replace the details with a summary instead.

Extraneous Content: For the position, we had the following candidates: Abagail Anderson, Ben Browning, Carly Cialdini, Dan Damesworth…[list 22 more names]. Of these candidates, we interviewed Dan Damesworth, Eli Ellsworth, and Sarah Storz.

Concise: For the position, we had 26 applicants, and we interviewed three of them: Dan Damesworth, Eli Ellsworth, and Sarah Storz.

Recap instead of Quote

Sometimes, you may be required to recount talk, whether that is a conversation, a discussion at a meeting, or even a heated debate. Recapping is a special summarization technique that captures the essence of what has been said or what has been done. It can be useful for documenting personnel issues and meeting minutes. Instead of providing a “transcript” of an interaction, you can be much more concise by capturing the main ideas of what was said or done.

Extraneous Content: In the last staff meeting, Danny recommended that we buy a new machine. Dora asked how much it would cost. Danny said it would be about $3,000. Leo jumped in and said that a good-quality machine would be closer to $4,500. Danny agreed but said that we might be able to get a discount from our supplier. Paul said that we shouldn’t be spending our money on machines when there could be more cost-efficient ways to get the work done. Morgan asked Paul for some examples…

Concise: In the last staff meeting, Danny recommended that we buy a new machine (~$3,000–$4,500). The staff discussed several ways the work could be done without the new machine. They voted against purchasing the machine at this time.

Communication Tip: Getting Concise with Data Visualizations

It has been said that a picture is worth ten thousand words. That adage holds true for business, too. If you have complicated data that includes a lot of data, a visualization is almost always more efficient than text.

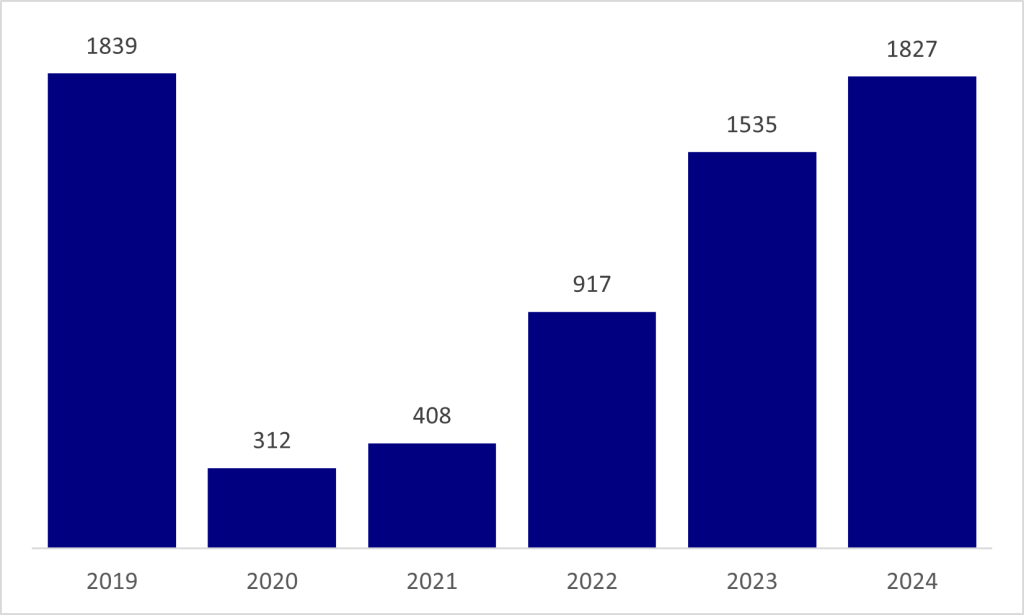

In the one simple graphic below, you can see what the membership enrollment was for six consecutive years. You can also quickly spot the highest enrollment and lowest enrollment, as well as a general trend. More complex graphics can contain even more data in the same amount of space.

You will learn more about effective data visualizations in Chapter 5. But even now, it is easy to see that this chart tells a story very concisely.

Monthly Memberships Have Nearly Returned to Pre-COVID Levels |

|