Persuade Ethically

Before getting too far into the how-to of developing persuasive messages, it is important to step back and consider the big picture of ethical persuasion. Ethics are systems of moral, social, and cultural values that govern behavior, beliefs, and interactions. Put another way, ethics are a standard of what is considered right or wrong.

Ethics can be shaped by personal and social backgrounds, family, religious beliefs, and community. In business contexts, additional sources of ethical guidelines can include laws, industry-based codes of ethics, and company policies.[1] For example, accountants are required to follow federal, state, and local laws regarding financial reporting, as well as the Association of International Certified Professional Accountants’ Code of Professional Conduct and the policies of the respective accounting firms where they work.

Being ethical means knowing standards of right and wrong that are appropriate to the context and then upholding those standards. Specifically, ethical business professionals do more than just ask, “Am I legally allowed to do this?” They ask, “Is doing this the right thing to do?”

While it is important to be an ethical communicator at all times, it is even more critically important to uphold ethical standards when you are persuading someone. That is because when you are engaging in persuasion, you are attempting to influence someone’s beliefs and behaviors. Whatever actions are taken as a result of your persuasion attempts can have real implications—for your receiver, for the business, for stakeholders beyond the immediate exchange, and for future decisions as well.

In this section, you will be introduced to two big picture guidelines to guide your thinking about being an ethical persuader: thinking about your long-term goals and thinking about your receiver.

Your Turn: What is Your Profession’s Code of Ethics?

Many business professions are guided by a code of ethics. There are industry-wide codes for many business professions, such as accountants, advertising professionals, real estate agents, procurement managers, attorneys, and the list goes on. Additionally, businesses frequently create their own codes of ethics or ethics-based policies.

Based on your career plans, what codes of ethics can you find? You might look up codes of ethics for your profession. You might also look up codes of ethics for your company or a company where you’d like to work.

Questions to Ponder

1. What are the primary principles of your professional code of ethics?

2. How is communication addressed in your professional code of ethics?

3. Which ethical standards surprised you most?

Think About Long-Term Goals

Whatever your specific instrumental goal is, when you are persuading a receiver, your underlying goal is to be successful in your attempt to influence. But taking a “win at all costs” approach to persuasion—an approach where you take any and every action necessary to win, regardless of whether it is ethical or not—is an unwise move in business.

Let’s go back a moment to the foundational principles of business communication. Business communication has three goals: an instrumental goal, a relational goal, and an identity goal. While relational and identity goals are idiosyncratic and set by the communicator, they should never include unequivocally negative goals.

Therefore, should a “win at all costs” approach lead you to apply unethical influence tactics, even as you achieve your instrumental goal, you could undermine your relational goal and identity goal.

For instance, consider Phoebe, who wants to persuade her company to develop a new product line. If Phoebe is deceptive in her presentation of claims and data, she might “win” the argument and meet her instrumental goal. But should company leaders determine that Phoebe intentionally falsified, fabricated, or withheld critical information, leaders likely will feel betrayed and disrespected, which will damage Phoebe’s relationship with them. Furthermore, they almost certainly will view her as dishonest and unethical, which will tarnish Phoebe’s reputation.

Not only will damaged relationships and a tarnished reputation make Phoebe’s future persuasive attempts much more difficult, it is possible that her current persuasive attempt still may fail. That is, once Phoebe’s deception is detected, the leaders may change their course of action and rescind any earlier commitment to the new product development.

The moral here is that any short-term gains from unethical attempts to influence will be offset, if not heavily outweighed, by long-term losses. In contrast, ethical persuasion can build long-term trust and, when successful, can create lasting changes in beliefs and actions. Therefore, you would be well-served to “lose” some persuasive attempts throughout your career than you would be to use unethical tactics to secure short-term gains.

Think About Your Receiver

A receiver-centric point of view on persuasion provides a good vantage point for understanding expectations about ethics. Receivers generally want to make the best decision possible. To do that, they need all of the information necessary to make a decision and they need the freedom to make the decision they think is best.

However, not all attempts to influence decision-makers are ethical. Below we describe three expectations receivers have for influence attempts and identify ways in which unethical influencers can violate those expectations. The use of the terms “influence” and “influencer” are intentional and used to draw attention to the fact that the unethical tactics described below do not have a place in ethical persuasion efforts.

Receivers Expect the Truth

Receivers rely on honest information to evaluate claims and make good decisions. Therefore, they expect the truth in persuasive appeals.

Unethical influencers, however, can resort to deception to achieve their instrumental goal. Deception is an unethical attempt to induce agreement by making an untruthful case. Deception can serve the purpose of making an alternative appear better than it really is or supporting a claim when there is not sufficient support. There are three primary types of deception common in business.

Lying occurs when an unethical influencer presents as true claims and/or evidence that are known to be false. An example of lying is knowing that a product breaks after three months of use, but telling your receiver that it will last five years.

Fabrication involves creating or manufacturing information to be presented as true. An example of fabrication is writing several product reviews and then presenting them as evidence of having highly satisfied customers.

Omission is the intentional exclusion of negative or unflattering information that is relevant to the decision-maker. An example is knowing that several people have been hurt using your product, but not alerting your receiver about the problems.

Receivers Expect Straightforwardness

Receivers often are confronted with multiple claims and mountains of evidence as they evaluate persuasive attempts. Being able to trust information that is presented to them on-face value reduces their cognitive load and helps them make decisions more readily. Therefore, they expect straightforwardness in persuasive appeals.

Yet, unethical influencers sometimes resort to manipulation. Manipulation is an unethical influence technique used to induce agreement by distorting the truth. Here are two common types of manipulation that occur in business contexts.

Cherry picking involves presenting only selective evidence instead of representative information. For example, when only a few customer service reviews are favorable and most are negative, sharing only positive reviews—even though they are truthful reviews—would be cherry picking.

Misrepresentation occurs when unethical influencers present information unclearly, incorrectly, or in opposition to normal conventions with the intention of getting receivers to view the evidence in a particular way.

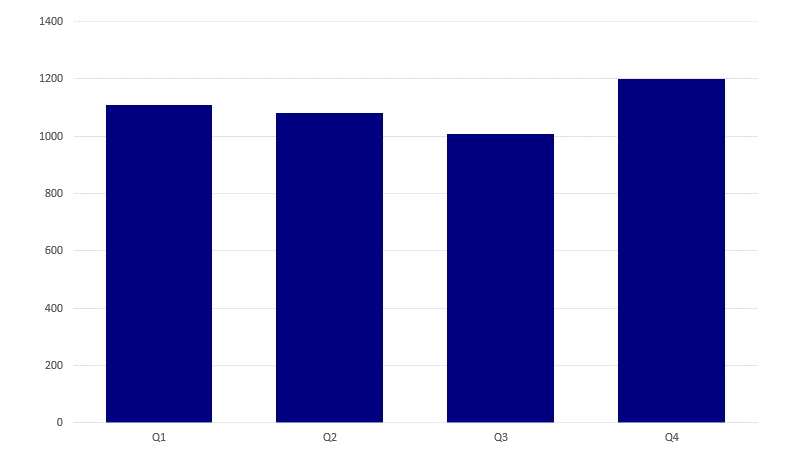

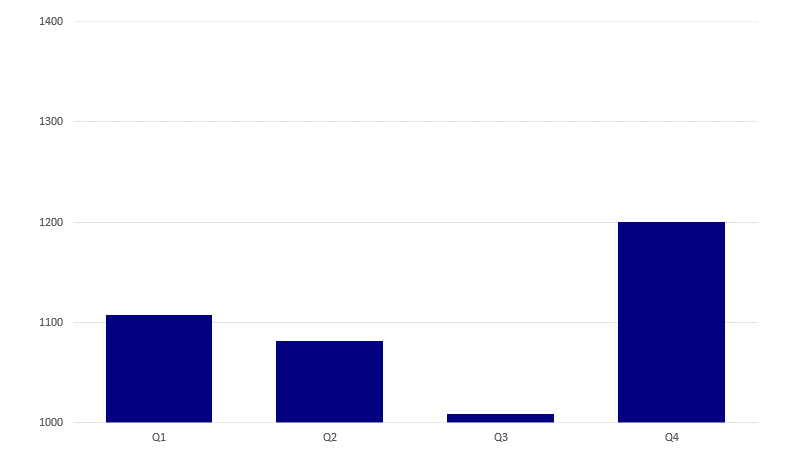

There are numerous ways unethical influencers can misrepresent data. For instance, they might present facts without context (claiming “We are ranked in the top three financial services companies in the city,” but not mentioning that there are only three financial services companies), omit relevant details (claiming “Our employees are paid well, earning $18 per hour,” but not mentioning that only $8 is paid by the company and the other $10 is estimated based on average tips), or use deceptive data visualizations (such as the one in Figure 1 below).

|

|

| Figure 1. Unethical influencers can manipulate interpretations of data by creating charts and graphs that mislead. One common trick to look for is the truncated Y axis. A truncated axis occurs when the numbers on the vertical axis begin at a number other than 0. In the example above, the two charts show identical data. But fluctuations that appear relatively small with a full axis (the chart on the left) look very large with a truncated axis (the chart on the right). | |

Receivers Expect Freedom to Choose

Finally, receivers need to retain their agency, which is their capacity to make a decision of their own free will. By doing so, they know that they are not being forced to do something that goes against their own interests or the interest of the greater good. Therefore, receivers expect that persuaders will respect their right to make a free choice when presented with the facts.

But unethical influencers do not respect their receivers’ right to make a decision and instead may resort to coercion. Coercion is an unethical influence technique used to induce agreement through limiting or eliminating the ability of receivers to make decisions based on the merits of the appeal. There are several ways in which someone could coerce a receiver.

Threats are intentions to deliver a negative consequence if someone does not agree to the persuasive appeal. Threats can be explicitly stated or implied. They might include the loss of employment, friendship, or future opportunity. They might also include threats to reveal secrets, discredit an individual, or retaliate if a decision isn’t made in the desired way.

Promises are the reverse of threats. But instead of coercing through negative outcomes, unethical influencers induce agreement through a commitment to give something valued in exchange for making the desired decision. Promises can include favors, preferential treatment, money, or anything else of value. Two types of promises made in business contexts are bribes (payments made in advance and in exchange for a desired decision) and kickbacks (pre-negotiated payments made after a decision). In many cases, bribery and kickbacks are illegal. But in all cases, they interfere with a decision-maker’s ability to make unbiased decisions.

Intimidation involves exposing and exploiting receivers’ vulnerabilities and making them feel that they do not have the power to make a different decision than the one desired by the unethical influencer. Intimidation can arise from formal hierarchy (someone being told, “because I’m your boss and I told you to”) to informal relationships such as bullying.

Collectively, receivers’ expectations provide general guides for ethical persuasion: Be completely honest, do not attempt to mislead, and do not interfere with your receiver’s right to decide. You also can use the FAIR Test, described in the Communication Tip box below, as a way to evaluate your own communication efforts.

Communication Tip: The FAIR Test for Ethical Persuasion

If you want to evaluate the ethics of your persuasive attempts, you can use the FAIR Test, which was developed as a standard for professional communication by business communication professor Peter Cardon.[2] When you write a persuasive message you can ask yourself the following questions.

Facts. Am I presenting the facts accurately and completely?

Ethical communicators use accurate information, include all relevant information, and present their evidence so that they do not mislead or deceive their receivers.

Access. Am I making my motives and reasoning accessible?

Ethical communicators are accessible when they are transparent with their receivers. They are upfront about their motivations, declare any conflicts of interest, describe how they obtained their information, and share their reasoning with their receivers.

Impacts. Am I making a positive impact?

Ethical communicators consider the impact they have on their receivers and all other stakeholders affected by their persuasion attempts. They make concerted efforts to minimize negative impacts and maximize positive impacts.

Respect. Am I respecting my receiver?

Ethical communicators respect their receivers. They know that others can have different views and accept that receivers are free to choose. They don’t attempt to coerce people to make a decision and don’t take advantage of others.

- Laws are guidelines that clearly demarcate right from wrong. But the law is only one small part of ethics. There are plenty of things that may be legal, but not ethical. For example, it may be legal to gossip about a coworker, but that doesn’t make it the right thing to do. ↵

- For a full write-up, see: Peter Cardon, Business Communication: Developing Leaders for a Networked World (New York: Mc-Graw Hill, 2024). ↵

a broad category of unethical influence techniques that use false claims and evidence to induce agreement

a type of deception in which an unethical influencer says something patently untrue

a type of deception in which an unethical influencer manufactures false evidence that is presented as true

a type of deception in which an unethical influencer intentionally excludes relevant negative information

a broad category of unethical influence techniques that distort the truth to induce agreement

a type of manipulation in which an unethical influencer presents selective evidence instead of representative evidence

a type of manipulation in which an unethical influencer presents information in an unclear way so receivers have a difficult time verifying the truth

a broad category of unethical influence techniques that use power to limit or eliminate the receiver's decision-making agency

a type of coercion in which an unethical influencer states or implies an intention to follow-up with negative action if a decision-maker does not make the desired decision

a type of coercion in which an unethical influencer offers to give something of value in exchange for agreement

a type of coercion in which an unethical influencer induces agreement by exploiting the receiver's vulnerabilties