Apply Advanced Persuasion Techniques

When you master your ability to set your overarching position and structure your supporting argument, you can apply advanced persuasion techniques to bolster your effectiveness. While there are numerous persuasion theories that can inform your strategy, here we cover three basic approaches that can be used in business writing.

As you get acquainted with each of these approaches, you will see that they rely heavily on being receiver-centric. You will need to know a lot about your receiver to be able to determine your best course of action.

Adjust to Your Receiver’s Anchor Point

Persuasion can be hard. Especially when you try to persuade people to believe or do something very different than they are used to, you may find that they are resistant to change. Chances are, even you might be resistant to other communicators’ attempts to persuade you. It’s simply part of human nature.

Because of this resistance, persuasion is frequently most effective when it happens in steps. That is, you might have to engage in several persuasive attempts—with each step advancing your persuasive goal a little further—to get your receiver to adopt your point of view or take action on your proposal.

The question, then, is how do you know when you can go for the full request or if you should take it in steps? Social Judgment Theory provides a useful way to think about setting your overarching persuasive position.[1]

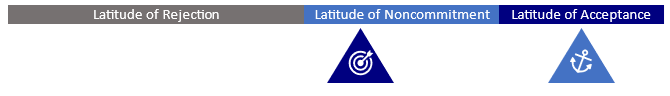

The basic premise of Social Judgment Theory is that every person holds a collection of beliefs, and they fall into three zones or “latitudes.” The latitude of acceptance includes all positions that people find true and reasonable, the latitude of rejection includes all positions that people find objectionable, and the latitude of non-commitment includes the remaining positions that people are neutral toward. Additionally, every person holds an anchor point, which represents their preferred position along that continuum.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise then to learn that if you make a request in someone’s latitude of rejection, you will likely be rejected. But if you only forwarded positions in that receiver’s latitude of acceptance, you wouldn’t really be persuading, either. So, for the maximum persuasive impact, your goal is to set a persuasion target that is as close to your target goal as possible but still within your receiver’s latitude of non-commitment.

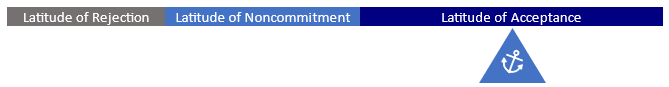

Because anchor points are not set in stone, as you persuade your receiver, his or her anchor points will likely shift. So, even though you may not reach your ultimate goal for persuasion in the first attempt, by influencing your receivers’ beliefs, you will expand their latitude of acceptance, shift their anchor point, and possibly even shrink their latitude of rejection. See Figure 3.

| Before Persuasive Attempt

After Successful Persuasive Attempt Figure 3. Strategic persuasion involves understanding your receiver’s latitudes of acceptance, rejection, and non-commitment. By targeting your instrumental goal within the latitude of non-commitment (versus the latitude of rejection), you will increase your likelihood of success in your persuasion attempts. Successful persuasion attempts can ultimately alter the boundaries of your receiver’s latitudes and shift anchor points, making additional progress possible. |

Appeal Differently to Expert and Novice Receivers

Another strategic approach to persuasion involves developing your argument differently depending on whether your receiver is an expert or a novice decision-maker.[2] Communication expert Richard Young explains how the knowledge and experience level of receivers significantly impact how they interpret and act on your messages.[3]

Specifically, expert decision-makers are those who are experienced at making a particular kind of decision. Over time, they will have developed schemas for decision-making. A schema is a mental checklist that includes all the main criteria they use to make a particular kind of decision. When faced with persuasive messages, expert decision-makers actively evaluate messages for information that addresses each criterion. Then, using matrix thinking, they essentially build a mental image of a table that compares one or more proposals against their schema.

Because expert receivers are highly rational and efficient in their approach, the most persuasive messages enable them to make their decision as quickly as possible. In fact, expert receivers often view messages that address irrelevant points as less effective and less persuasive. That means that you should make sure that you have a complete understanding of your receiver’s decision-making criteria, concisely address all criteria, and exclude any claims about criteria outside the schema.

In contrast, novice decision-makers are less experienced at making particular kinds of decisions and likely have not developed schema. Thus, their approach to decision-making may be more emotional, intuitive, or passive. This does not mean that novice decision-makers are unable to make good decisions. Instead, it means that it may take longer for them to evaluate available criteria, and they may be influenced by a wider range of considerations.

To maximize the effectiveness of a persuasive appeal to a novice decision-maker, you should explicitly identify the criteria that should be used to evaluate your proposal and then demonstrate how your proposal meets those criteria. Also, knowing that novice decision-makers are more likely to be influenced by multiple considerations will help address and dispel counterarguments. If you are thinking that all these steps will make persuasive arguments for novice decision-makers longer, you are right.

Balance Logical and Emotional Appeals

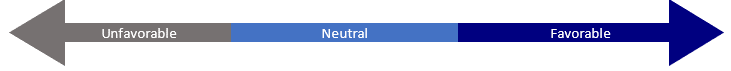

A third approach to persuading receivers is to strike the right balance of logical and emotional appeals. The right mix of appeals is dependent upon where your receiver stands on a particular matter. As described earlier, a receiver can be favorable, unfavorable, or neutral. That relative positioning toward your persuasive position will influence which kinds of evidence and claims will be most effective. Communication experts Jo Sprague, Douglas Stuart, and David Bodary have provided a good general framework for determining the right mix. See Figure 3.[4]

For favorable receivers, they likely already agree with you—at least in principle. So, your task in persuading them is not necessarily to get them to believe something but instead to motivate them to act on something that you’ve said. Therefore, instead of spending a lot of time on logical appeals, you can introduce emotional appeals to intensify your receivers’ favorability, rally their support, or get them more involved.

But emotions don’t always work that way. With unfavorable receivers, emotional appeals will likely decrease your likelihood of success. Because unfavorable receivers are starting from a position opposed to your goal, they need sound logic and strong evidence to be moved. The use of emotional appeals will likely be viewed as a weak attempt to persuade, a lack of credible evidence, or possibly even an attempt to manipulate. For unfavorable audiences, then, it is better to stick to facts and logic.

For neutral receivers, chances are that you will need a mix of logical and emotional appeals. But the right mix will depend on whether your receivers are neutral because they are undecided, uninformed, or simply uninterested. Undecided and uninformed receivers should be presented with a full case of evidence that presents all sides of the argument and is heavily geared to logic. Uninterested receivers will also need a lot of logical appeals, but introducing some emotional appeals may help motivate them to care about your appeal.

|

||

| Logic | Logic and Emotion | Emotion |

Communication Tip: Communicate with Confidence

When it comes to persuasion, how you say something can be just as important as what you say. In particular, communicating confidently and passionately sends subtle cues to your receiver that help you be more persuasive. Below are some tips for how to communicate with confidence.

Strike Tentative Clauses

Tentative clauses include anything that (unintentionally) signals uncertainty or a lack of confidence. It can include expressions like “I believe,” “I think,” and “in my opinion.” When people read tentative clauses, they get a subtle signal that the communicator isn’t completely sure. That, in turn, can lead them to be less confident in the claim as well. So check your messages for tentative clauses and then eliminate them.

Example: I think this will be the best option for the company.

Improved: This will be the best option for the company.

Trim Empty Hedges

Hedges are words that are used to exercise caution or make a statement less forceful. Sometimes, using hedges is necessary and ethical in persuasion, such as when you are being honest and accurate about a relationship. For example, there is a difference between saying something will happen versus something might happen. But sometimes, hedges slip into writing unintentionally.

Be on the lookout for words that minimize your certainty: maybe, perhaps, possibly, sometimes, fairly, usually, might, could, actually, and other similar words. Each time you see one of those words, read your sentence carefully. Is the hedge necessary to convey the truth? Then keep it in. Is it there as a filler word? Then, strike it or replace it with a stronger word.

Example: Implementing these three cost-saving measures maybe could save us $1 million annually.

Improved: Implementing these three cost-saving measures is projected to save us $1 million annually.

Express Your Passion

It is usually easier for receivers to evaluate a communicator’s passion when they are speaking rather than writing, as they can rely on tone of voice, body language, and other nonverbal cues. But you can demonstrate passion in your writing, too. One way to do it is to explicitly state that you are passionate. Expressions like “I care deeply about this issue” or “This matter is important to me” directly communicate your passion. You can even share a concise story about why you are passionate. Of course, you should reserve expressions of passion for when you are genuinely passionate.

Example: This new employee wellness program will enable us to build a healthier and happier workforce.

Improved: We are passionate about this new employee wellness program, which will enable us to build a healthier and happier workforce.

Avoid Exclamation Points

Be careful using exclamation points in business contexts. While exclamation points might help you convey your enthusiasm in personal communication, using them in business can backfire and raise questions about your seriousness. When it comes to persuasion, it is usually best to leave out all exclamation points.

Example: Our software platform is easy to use!!!

Improved: Our software platform is easy to use.

- Social Judgment Theory was developed decades ago by social psychologists Muzafer Sherif and Carl Hovland. You can read more in one of the original publications: Muzafer Sherif and Carl Hovland, Social Judgment: Assimilation and Contrast Effects in Communication and Attitude Change. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1961) ↵

- To be clear, the differentiation between expert and novice receivers is not about intelligent versus not intelligent or about general experience versus general inexperience. Instead, differentiation refers to people's experience and expertise in making particular kinds of decisions. For example, someone who works in human resources is likely an expert at making hiring decisions but a novice at making decisions about purchasing a new software system. In contrast, someone who works in procurement is likely an expert at making large purchases but may be more novice at making hiring decisions. ↵

- If you are interested in persuading decision-makers in a variety of business contexts, you can read Richard Young, Persuasive Communication: How Audiences Decide, 2nd ed. (New York, NY: Routledge, 2016) ↵

- The framework for balancing logical and emotional appeals was originally developed for persuasive public speaking. However, the basic principles hold whether speaking or writing. For more information, see Jo Sprague, Douglas Stuart, and David Bodary, The Speaker's Handbook, 12th ed. (Boston, MA: Cengage, 2019) ↵

a theory developed by social psychologists Muzafer Sherif and Carl Hovland that explains attitude change processes

experienced decision-makers who have developed and use schemas for decision making

a mental checklist of the criteria used to make a particular decision

a less experienced decision-maker who tends to rely on emotion, intuition, and/or passive information seeking to make a decision