Chapter 3: Metacognition

Learning with style

Imagine this scenario: You’ve entered a paper airplane competition where the best paper airplane maker will receive $1000. You are given a blank piece of paper and are told to build a paper airplane. Before you begin, you have to choose how you’ll learn to build a paper airplane from these four options:

- Watch a video with no sound showing you how to build the airplane.

- Listen to someone describe how to build the airplane.

- Read a step-by-step list for how to build the airplane.

- See a picture of the airplane and you make a guess at how to build it.

To boost your odds of winning that $1000, which instructional method would you choose?

Maybe you’re thinking, “why can’t I have a video with sound and closed captions that also shows me what the end product looks like? I like listening to instructions but also like to be able to see what they are doing and what it’s supposed to look like when it’s done.” Perhaps, you are saying to yourself, “I actually don’t know what one I would pick.”

Whether you know immediately which instruction method you’d pick or don’t see a method that feels right to you, the primary thing to know is that sometimes you’re going to be given flexibility and sometimes you’re not. So, you need to become aware of the various ways that you can accomplish your assignments and learn information in the most effective ways.

The fun thing about college is that you get to have more control over your situations. That is, for the most part, you get to decide how you want to engage with your homework and when. A huge part of homework, though, and by extension, learning, is figuring out the best ways to take in and process the information being taught to you. Therefore, this chapter is going to ensure you have the best skills and strategies to be successful in the learning process.

Learning Objectives

This chapter will:

- Describe what metacognition is

- Explain how learning works and supports you holistically

- Discuss strategies for how to learn best for you

- Define information literacy and the key skills and concepts associated with information literate learners

- Explain why information literacy matters as a college student, a professional, and a citizen

- Identify on and off campus resources that can support your learning

Metacognition and How It Helps You Succeed

“Learning is not an event, but rather a process that unfolds over time” (Stahl et al., 2010).

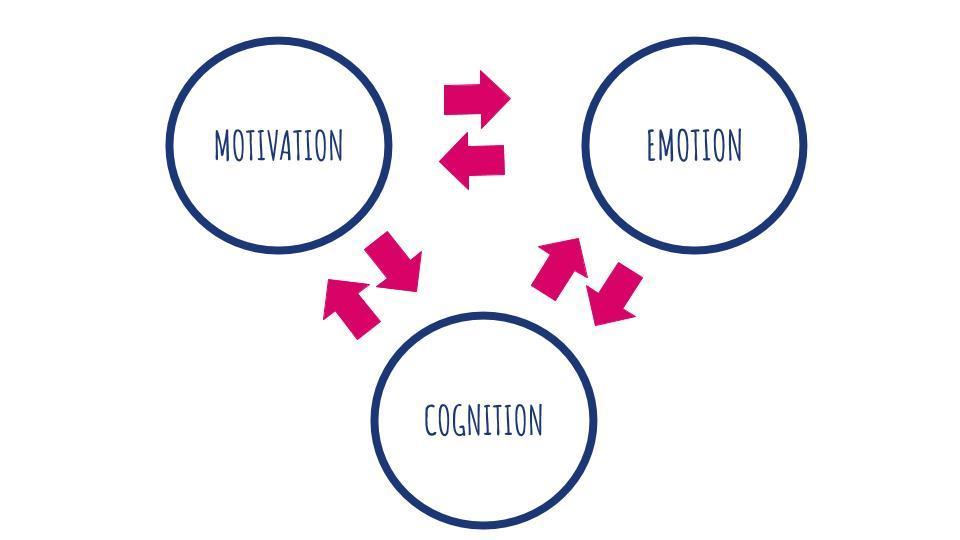

The world is not static. It is dynamic and uncertain. Learning enables you to adapt to your uncertain environments and succeed in a competitive environment. At EKU, we define learning as a process rather than a product that can lead to significant change over time. This change is influenced by three interrelated areas: (1) Motivation (2) Emotion and (3) Cognition (Figure 1).

Figure 3.1 Interrelated process that guides learning (Source: Beardsley, 2020).

Motivation and emotion both have the same underlying Latin root “to move.” Motivation and emotion are words that describe things that “charge,” “drive,” or “move” our behavior. When we experience emotions or strong motivations, we feel the experiences (Stangor & Walinga, 2014). Motivation and emotion are crucial for learning because, when working together, they enable you to truly grasp and apply new information and abilities (Boekaerts, 2010).

Importantly, motivation and emotion are complex and wrapped up within one another. Think about why you are currently in college. Are you here because you enjoy learning and want to pursue an education to make yourself a more well-rounded individual? If so, then you are intrinsically motivated. However, if you are here because you want to get a college degree to make yourself more marketable for a high-paying career or to satisfy the demands of your parents, then your motivation is more extrinsic in nature. People aren’t just one or the other. Our motivations are often a mix of both intrinsic (example: love for what you do) and extrinsic factors (example: getting paid), but the nature of the mix of these factors might change over time.

So, what is cognition?

Upon waking each morning, you begin thinking and contemplating the tasks that you must complete within the day. In what order should you run your errands? Should you go to the gym, work, or the grocery store first? Can you get these things done before you head to class, or will they need to wait until class is done? These thoughts are one example of cognition at work.

Simply put, cognition is thinking, and it encompasses the processes associated with perception, knowledge, problem solving, judgment, language, and memory.

When brought together, motivation, emotion, and cognition are important aspects of metacognition. Metacognition is the awareness of one’s thought processes and an understanding of the patterns behind them. The metacognition cycle involves:

- Assessing the task

- Evaluating strengths and weaknesses

- Planning the approach

- Applying strategies

- Reflecting

Watch the video below to learn more about metacognition!

As the video points out, metacognition is a cycle that tends to become easier to access and repeat the more you engage with it. That’s why at first learning feels hard. Because learning is hard. However, metacognition – knowing how to learn – is one way to make it a little bit easier.

Metacognition is not a tool that you leave behind at EKU once you graduate. Research (Lovett et al, 2023) demonstrates that knowing learning is a process that you can improve upon means you will take this with you beyond your time at EKU. Critically, it will help you in your future career and personal life.

Thinking Skills

So what are the various types of thinking skills, and what kind things are you doing when you apply them? In the 1950s, Benjamin Bloom developed a classification of thinking skills that is still helpful today; it is known as Bloom’s taxonomy. He lists six types of thinking skills, ranked in order of complexity: knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. Anderson and Krathwhol (2001) updated Bloom’s Taxonomy with details outlining each skill and what is involved in that type of thinking, as you can see in the figure below.

| Thinking Skill | What It Involves |

|---|---|

| 1. Remembering and Recalling | Retrieving or repeating information or ideas from memory. This is the first and most basic thinking skill you can develop (starting as a toddler with learning numbers, letters and colors). |

| 2. Understanding | Interpreting, constructing meaning, inferring, or explaining material from written, spoken, or graphic sources. Reading is the most common understanding skill; these skills are developed starting with early education. |

| 3. Applying | Using learned material or implementing material in new situations. This skill is commonly used starting in middle school (in some cases earlier). |

| 4. Analyzing | Breaking material or concepts into key elements and determining how the parts relate to one another or to an overall structure or purpose. Mental actions included in this skill are examining, contrasting, or differentiating, separating, categorized, experimenting, and deducing. You most likely started developing this skill in high school (particularly in science courses) and will continue to practice it in college. |

| 5. Evaluating | Assessing, making judgements, and drawing conclusions from ideas, information, or data. Critiquing the value and usefulness of material. This skill encompasses most of what commonly referred to as critical thinking; this skill will be called on frequently during your college years and beyond. Critical thinking is the first focus of this chapter. |

| 6. Creating | Putting parts together or reorganizing them in a new way, form, or product. This process is the most difficult mental function. This skill will make you stand out in college and is in very high demand in the workforce. Creative thinking is the second focus of this chapter. |

Figure 3.2 – Types of Thinking Skills

All of these thinking skills are important for university work (and life in the “real world,” too). You’ve likely had a great deal of experience with the entry level thinking skills. The mid level skills are skills you will get a lot of practice with in university, and you may be well on your way to mastering them already. The upper level thinking skills are the most demanding, and you will need to invest focused and intentional effort to develop them.

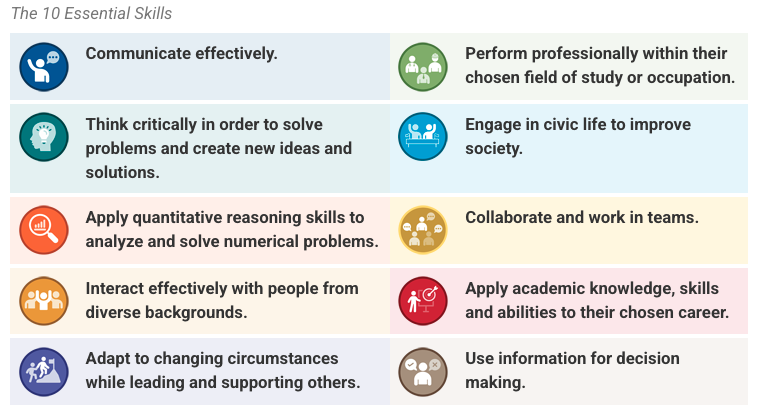

These thinking skills overlap with and transfer to the Kentucky’ Graduate Profile’s list of 10 Essential Skills. These 10 skills, which will be discussed at length later in the textbook, were identified as the 10 primary skills that employers around the state of Kentucky are wanting from employees. As you can see in Figure 3.3 below, many of these skills you develop through your course work are also skills that will assist you in the workplace.

Figure 3.3: Kentucky’s Council for Postsecondary Education’s 10 Essential Skills

Mechanics of Learning

Reconstructing experiences in your brain (learning) uses a lot of resources, including energy (from food) and biological material (neurons). However, these resources are limited, including the space available for the brain in the skull. Thus, brains prioritize what we learn and what we store in our memory. As a result, most information your brain encounters is filtered out and lost.

For example, have you had an experience where you feel motivated to learn and make an effort but you are unable to because you don’t have the energy or the bandwidth? This means that you have limited resources – less energy from food and less neurons to fire and make connections. Scientists have isolated a mechanism to remember the main barriers to learning, and by doing so, we can learn of mechanisms to combat these barriers. The acronym used to combat the main barriers to learning is WARP:

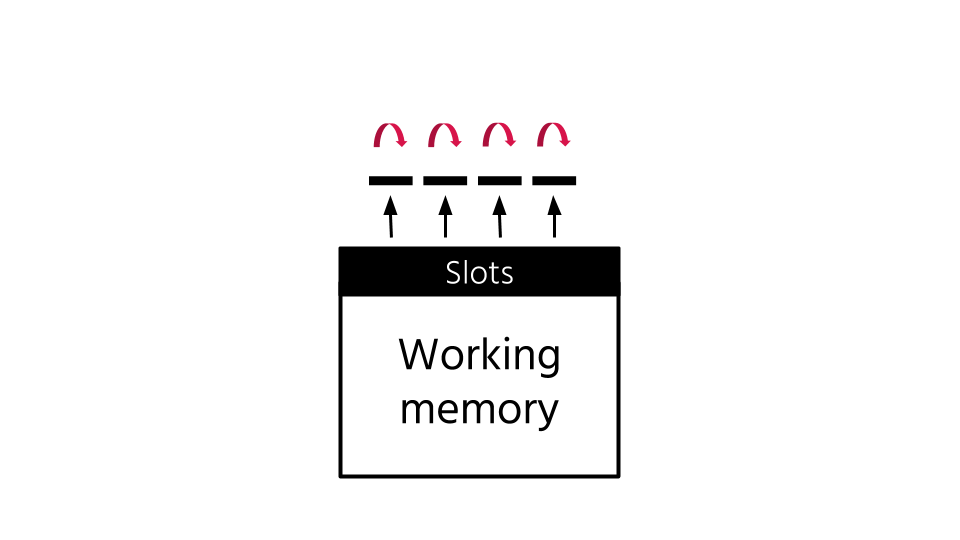

Working Memory – refers to our capacity to temporarily hold and manipulate a limited amount of information in an easily accessible state. Research indicates that working memory can typically manage around 4 distinct “chunks” of information at any given time. Our ability to hold on to information in working memory is highly temporary, usually lasting only 10 to 15 seconds unless it is actively used, rehearsed, or otherwise processed. For instance, when you’re listening to a lecture, your working memory is constantly engaged in processing incoming auditory information, allowing you to comprehend current sentences and relate them to previous ones, even if you’re not taking notes. However, a 20-minute lecture would quickly overwhelm working memory, requiring the active processing and transfer of information to other memory systems.

Figure 3.4 A depiction of the limited capacity of working memory (Beardsley, 2020).

Attention – can become distracted or depleted. If we’re not paying attention, the information does not enter our memory system in a retrievable manner, or it is encoded in a deficient manner. In the example above, whilst listening during a lecture if there is a lack of focus and attention the working memory, short-term memory and therefore long-term memory is compromised. In the next section, we will discuss specific ways to practice attention.

Retrieval – is accessing the information stored from our memory. If you do not practice recalling your stored information, your long-term memories become inaccessible as the routes you made to creating new information become buried. Think of it as erasing and deleting old music on a hard drive. In the next section of this chapter we will discuss specific ways to practice retrieval.

Prior Knowledge – can be thought of “as stored knowledge and beliefs about the world that have been acquired by an individual” (Brod, Werkle-Bernger & Shing, 2013). As our learning builds on what is already there, our pre-existing or prior knowledge is one of the most significant determinants of subsequent learning. In the example above, before attending a lecture on a topic, having read the chapter addressing the topic and completing any assigned reading will only enhance the number of slots that your working memory can hold!

Sleep to Learn

Recent research reveals the critical role sleep plays in learning (Tamaki & Sasaki, 2022). An important discovery showed a mechanism during sleep where the activity of neurons – types of nerve cell in the brain and brain stem – related to what had been learned during the day. When we go through deep sleep (rapid eye movement or REM sleep), we ‘replay’ what we have learned in the brain areas of the hippocampus and the neocortex. This replay has been shown to play an important role in memory consolidation (Ji & Wilson, 2007; Breton & Robertson, 2013). Memory consolidation is where a temporary memory is transformed into a long-term memory (LTM). These findings show the importance of good sleep health to memory consolidation and learning. Moreover, while we don’t necessarily have to sleep during the day, we do need to give our brains a break – as breaks provide an opportunity to practice memory consolidation. Examples of taking “brain breaks” include: exercising, taking a short nap (15-30 minutes), meditating and unplugging from all devices and distractions.

Attention to Learning

We can think of attention as a spotlight. Unlike working memory, we do not have four available slots/spotlights for attention. There is only one, single spotlight of attention – a single beam of light. What we shine it on – internally or externally – is what we pay attention to. We cannot integrate information that we do not pay attention to! It is important to pay attention to what you pay attention to, as this is what you integrate into your brain’s memory.

Hari (2021) interviewed experts about managing your attention:

Professor Earl Miller, a neuroscientist at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, explains ‘your brain can only produce one or two thoughts’ in your conscious mind at once. That’s it. ‘We’re very, very single-minded.’ We have ‘very limited cognitive capacity’. But we have fallen for an enormous delusion.

The average teenager now believes they can follow six forms of media at the same time. When neuroscientists studied this, they found that when people believe they are doing several things at once, they are juggling. ‘They’re switching back and forth. They don’t notice the switching because their brain sort of papers it over to give a seamless experience of consciousness, but what they’re actually doing is switching and reconfiguring their brain moment-to-moment, task-to-task – and that comes with a cost.’

There is a name for this: it’s called the switch-cost effect! For example, let’s say you are working on a homework assignment, and you receive a text, you glance over it for three seconds – and then you go back to your assignment. In that moment, your brain must remember what you were doing before, and you have to remember what you thought about it. When this happens, the evidence shows that ‘your performance drops. You’re slower. All as a result of the switching.’ (par. 10)

Here is a great video that explains the same concept of why multitasking is more harmful than helpful:

Evidence-Based Learning Strategies

What does evidence-based mean? This means that there is a lot of research and repeated findings to back up this science! This section is about smart learning versus hard learning. Smart learning uses scientific evidence to spend less time, effectively sending information into long term memory.

Retrieval Learning or Active Recall

From a cognitive perspective, we can place learning activities into two broad categories: encoding activities and retrieval activities. Encoding related activities focus more on “putting information in” to long-term memory (memorization). Retrieval related activities focus more on “taking information out” of memory – i.e. practicing the extraction of information from our long-term memory. For example, when you listen to a professor, read articles, watch videos, create concept maps or write essays while looking at your notes, you perform encoding activities. On the other hand, when you complete practice tests, write learning journals, teach peers, create concept maps or write essays from memory without referring to your notes, you perform retrieval activities.

In short, when you complete activities without referring to your notes or the textbook, you are required to retrieve the information from your memory system. When you reconstruct memory systems, you automatically strengthen retrieval routes! Now, most students practice retrieval for the first time during their first quiz or exam; however, active recall should be practiced several times before an actual test, quiz, or exam in order to be successful.

How can YOU incorporate active recall?

Active recall can be easily incorporated into your current study in several ways. One method involves taking whatever learning resource you use—whether it be lecture slides, classroom notes, or the textbook and making a list of concise questions based upon the content and lecture objectives for the course. The next time you revise the topic, instead of re-reading your notes or textbook, go straight to the questions and answer as many as you can without reading your notes. If there are questions that you get wrong, refer to your notes and then try to re-answer the question correctly. Color-coding the questions based on whether you got them right (green) or wrong (red) is a helpful way of tracking progress. Integrating spaced repetition into your topics and questions is another scientifically validated way to boost memory retention (Butler, 2010). Try and make use of online question-based resources such as Kahoot!, practice quizzes at Khan Academy, Quizlet and your professor’s previous quizzes or exams (ask them if they have any!) before, during and after a study session.

| How to sample the Active Recall Strategy for a given topic or lecture | |

|---|---|

| How long? | What do I do? |

| 10 minutes | Take a short quiz on the topic in order to determine what you already know (Prior Knowledge). |

| 20 – 30 minutes | Review and study lecture notes, the textbook, or other class resources. |

| 10 – 15 minutes | Write down from memory all that you read in the form of short points. |

| 5 – 10 minutes | Take a break! |

| 10 – 15 minutes | Take a practice quiz on the topic without referring to notes or your textbook. |

| 5 minutes | Check your answers. See what you answered correctly, and review what questions you got wrong. Take a break, and repeat! |

Spaced Learning

How we schedule learning activities matters. Research shows that if you would like to move content into LTM, then distributing the practice of the content and learning is critical. Rather than intensively cramming right before the exam, a more effective strategy is to distribute your exam preparation over multiple sessions. This is known as spaced practice or spaced learning.

How can you incorporate spaced learning?

| Here is a sample schedule for a given topic/lecture! | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | The Next Day | After 3 Days | After 1 Week | After 2 Weeks |

| Initial study session followed by an active recall strategy. | Revisit and review with a practice test. | Revisit and review with a practice test. | Revisit and review with a practice test. | Revisit and review with a practice test. |

Congratulations! By this point, the topic/lecture that you are trying to learn will be in LTM!

Want to learn more? Watch this video on spaced learning techniques.

Studying at the last minute is never beneficial. The best way to learn effectively is to space out your studying sessions.

Teach what you learn

Finally, the learning-by-teaching effect has been demonstrated in several research studies. Students who spend time teaching what they’ve learned go on to show better understanding and knowledge retention than students who simply spend the same time re-studying. This is because teaching is a form of retrieval practice (active recall) and usually employs spaced learning. In this way, you succeed in practicing all three of the evidence-based strategies!

How can you teach what you learn?

- Learn the material as if you’re going to teach it to others.

- Pretend that you’re teaching the material to someone (Active Recall).

- Check if your teaching is accurate!

- Teach the material to other people/students (Spaced Learning).

- As you get better at this, work on-campus at one of the several tutoring centers to get paid whilst you learn yourself and help others.

Information Literacy

You interact with information daily. For class, you read textbooks, perform research, and interact with digital media. Outside of class, you consume and create content for social media, seek answers to questions, and read about issues that impact you directly. Information literacy is an important set of life skills that foster success in the personal, academic, and professional areas of your life.

What is information literacy?

Information literacy requires skills but also an understanding of how information is created and organized. Your attitude is also important. Information-literate individuals have the desire to find quality information and embrace traits like curiosity and persistence. The American Library Association defines information literacy as a set of integrated abilities that empower individuals with the following skills and knowledge:

- An ability to be reflective while seeking information.

- An understanding of how information is produced and valued.

- An understanding of how to use information to create new knowledge.

- An ability to participate ethically in communities of learning.

The Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education (ACRL, 2016) breaks information literacy skills and knowledge into six concepts. Woven together, the six concepts provide students with a robust set of information literacy abilities for success in college and beyond. Use the graphic below to read about each of the six information literacy concepts. Turn the cards over for a set of questions that will help you apply these concepts.

Why does information literacy matter?

In today’s complex information environment, the average user has access to over one billion websites and over one hundred million videos on YouTube. Millions of books, magazines, and articles are published every year. Finding the right information for the right purpose takes some skill and attention.

Information literacy is a life skill that will help you apply critical thinking and reflection to locate, evaluate, and use quality information. An information-literate individual embraces the research process (even when it’s messy), synthesizes information from multiple sources, and makes conscientious choices when sharing information. Start building your information literacy skills now and you will find yourself applying the ideas at school and work while empowering yourself to become an active citizen.

S.I.F.T: Evaluate Information in a Digital World

Within this complex information environment, you’re constantly encountering information that demands scrutiny, whether you’re scrolling through social media, checking the latest news, or diving into a class assignment. At EKU Libraries, you’ll find not only a wide range of credible resources—books, scholarly journals, academic research databases, and more!—but also expert assistance from our librarians. They’re information literacy experts, specially trained to help you navigate today’s complex information environment. The ability to critically assess both academic and online sources is more crucial than ever, and it’s precisely this essential skill that our librarians can help you develop.

Traditional evaluation checklists—focusing on things like domain (.com vs. .org), ads, typos, design, or citations—are often insufficient on their own. That’s why, as part of EKU Libraries’ commitment to your information literacy, we recommend instead starting with the S.I.F.T. method. This approach offers a more robust and effective way to evaluate information, both online and often in print. S.I.F.T. is an acronym for four simple yet powerful steps: Stop, Investigate, Find, and Trace.

|

Stop |

When you first encounter a source of information and start to read it—STOP.

Slow down as you move to the next step. |

|---|---|

|

Investigate the Source |

Don’t rely on what the source says about itself in an “About Us” section. Instead open multiple browser tabs and start looking into what others have said about the source:

A fact-checking site—like FactCheck, Snopes, Politifact, or Reuters— may help. |

|

Find trusted coverage |

Look for more—and potentially better—coverage of the topic:

Keep track of trusted news sources, but don’t rely on only the news sources that you always agree with; instead, try to look at all sides of an issue. |

|

Trace claims, quotes, and media back to the original context |

A lot of re-sharing and re-reporting happens online, and much of what we find on the internet has been stripped of context. Finding the original source of a story, video, image, or other content helps to determine credibility by establishing that context. For example:

|

Prefer a video introduction? Check out this video from EKU Libraries:

The S.I.F.T. approach was created by Mike Caulfield, a digital literacy expert who focuses on fake news and how to detect it. If you’d like to learn more about the S.I.F.T. method, EKU Libraries Evaluating Information: S.I.F.T. (The Four Moves) – Research Guide provides a more detailed look at the method with videos from Caulfield that walk you through each step.

EKU Resources to Support Your Learning

Bobby Verdugo & Yoli Ríos Bilingual Peer Mentor and Tutoring Center aka “El Centro” (Library 106)

El Centro offers bilingual tutoring and mentoring for students interested in multilingual and multicultural community building and scholarship. Tutoring is offered in a variety of languages including Spanish, German, Japanese, etc. Additionally, El Centro offers tutoring in subject areas such as social work, public health, sciences, anthropology, sociology, etc. El Centro provides a space to apply the skills learned in language and culture classes in real-world settings through volunteering or service-learning community engagement.

El Centro also offers mentoring services where students meet once a week with a peer mentor. Each student is assigned a mentor based on major, academic, or personal needs. Within each mentoring session, students can receive help with navigating college, class advising, schedule building, networking, interview skills, email best practices, applications, essays, resumes, cover letters, scholarships, etc.

Center for STEM Excellence (New Science Building Atrium)

We partner with students and instructors to support excellence in STEM teaching and learning. All services are free to current EKU students learning in any STEM courses and programs. Our resources include drop-in learning (tutoring) and skill-building workshops in science, technology, engineering, and math courses.

Sign up for a workshop or drop-in tutoring using this link: Center for STEM Excellence Portal

Student Spotlight

Student Spotlight

“I love education and academia and I knew I was always going to go to college. I would say many people don’t know it’s (college) for them until they try it out. The old college try. However, that can be difficult at times so I would just do what you think is best for your future!”

-Ellie Craft, English, Class of 2025.

Center for Student Accessibility (Whitlock 3rd Floor)

The Center for Student Accessibility (CSA) assists students by coordinating campus and program accessibility and providing support in attaining educational goals. Students requesting services, including deaf and hard-of-hearing students, must submit a completed application for services and current health-related documentation.

Applications, documentation guidelines, and additional information are available on the CSA website.

Appointments are made by calling (859) 622-2933 or emailing accessibility@eku.edu.

EKU Libraries

EKU Libraries is your hub for the learning support you will need to be successful at EKU:

- Need a place to focus? The Main Crabbe Library has spaces for individual and group study.

- Have a question about a library research assignment? One of our many qualified and friendly librarians is available to help you one-on-one in the library, via chat, or by scheduling a research appointment in advance.

- Prefer DIY help? Check out our Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) or YouTube tutorials.

- Tight on time? A library staff member can pull an item from their shelves and put it on hold for you to pick up at our Main Desk by using the “Request It” link.

- Taking classes online or at a distance? We have a vast array of online resources available 24/7, including books, articles, and videos. Also, if you need a print resource, we can mail items to off-campus students. For more details, see our FAQ on checking out books.

Math & Statistics Tutoring Center (Wallace Building 342)

The Math and Statistics Tutoring Center offers walk-in tutoring, online tutoring, and one-on-one dedicated help. The center also has the ability to record the tutoring sessions so you can review them at any time.

Resources for current students include practice tests, tips for overcoming test anxiety, strategies for developing study plans and much more.

Sign up for a tutoring appointment using this link: Math/Stats Tutoring Portal

Noel Studio for Academic Creativity (Crabbe Library)

Located in the Crabbe Library, the Noel Studio helps EKU students develop effective communication and writing skills through peer-to-peer meetings called consultations, which are available both in-person (on the EKU Richmond campus) and online (via Zoom). The Noel Studio also provides technology, spaces, and resources to help students complete their academic work.

Schedule a consultation using this link: Noel Studio Consultation Portal

Student Success Center (Crabbe Library Ground Floor 106D)

Located on the first floor of the Crabbe Library, the Student Success Center is designed to serve as a one-stop-shop where students can get assistance with an array of areas like coursework, financial aid, study skills, choosing a major, course registration, stress management, and much more.

Sign up for a workshop using this link: SSC Tutors Available

Summary

- Learning is a process that unfolds over time.

- Cognition encompasses the processes associated with perception, knowledge, problem solving, judgment, language, and memory.

- Sleep plays a critical role in learning.

- Metacognition is knowing how to learn by understanding and regulating your own thought processes—a cyclical skill involving assessing, planning, applying, and reflecting.

- The acronym used to combat the main barriers to learning is WARP (working memory, attention, retrieval, and prior knowledge).

- You cannot integrate information that you do not pay attention to.

- There is no such thing as multitasking. Your brain switches its attention based on how many tasks you perform at one time. This increases the likelihood of you not retaining much information.

- Key evidence-based learning strategies include: active recall, spaced learning, and teaching what you learn.

- Information literacy is critical to learning information that supports both your academic work and your general well-being.

- Whenever a source provokes a strong positive or negative feeling, that’s a sign to double-check the credibility of that information.

- El Centro, Center for Student Accessibility, EKU Libraries, Math & Stats Tutoring Center, Noel Studio for Academic Creativity, Center for STEM Excellence, and the Student Success Center all exist for FREE at EKU to support your learning.

References

Anderson, L.W. & Krathwohl, D.R. (2001). A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Boekaerts, M. (2010). The crucial role of motivation and emotion in classroom learning. The nature of learning: Using research to inspire practice, 91-111. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264086487-en

Breton, J., & Robertson, E.M. (2013). Memory processing: the critical role of neuronal replay during sleep. Current Biology, 23(18), 836-838. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2013.07.068

Brod, G., Werkle-Bergner, M., & Shing, Y. L. (2013). The influence of prior knowledge on memory: a developmental cognitive neuroscience perspective. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience, 7, 139.

Butler, A. C. (2010). Repeated testing produces superior transfer of learning relative to repeated studying. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 36(5), 1118. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019902

Caulfield, M. (2019, June 19). SIFT (The Four Moves). Hapgood. https://hapgood.us/2019/06/19/sift-the-four-moves/

Hari, J. (2022, January 2). Your attention didn’t collapse. It was stolen. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2022/jan/02/attention-span-focus-screens-apps-smartphones-social-media

Ji, D., & Wilson, M. A. (2007). Coordinated memory replay in the visual cortex and hippocampus during sleep. Natural Neuroscience, 10(1), 100-7. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn1825

Lovett, M. C., Bridges, M. W., DiPietro, M., Ambrose, S. A., & Norman, M. K. (2023). How learning works: 8 research-based principles for smart teaching (2nd ed). Wiley.

Stahl, S. M., Davis, R. L., Kim, D. H., Lowe, N. G., Carlson, R. E., Fountain, K., & Grady, M. M. (2010). Play it again: The master psychopharmacology program as an example of interval learning in bite-sized portions. CNS Spectrums, 15(8), 491-504. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852900000444

Stangor, C., & Walinga, J. (2014). Introduction to psychology-1st Canadian edition. BCcampus. https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontopsychology/

Tamaki, M., & Sasaki, Y. (2022). Sleep-dependent facilitation of visual perceptual learning is consistent with a learning-dependent model. Journal of Neuroscience, 42(9), 1777-1790. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0982-21.2021

Attributions & Licenses

Parts of this chapter are adapted from the following sources:

First Year Seminar © 2022 by Kristina Graham, Rena Grossman, Emma Handte, Christine Marks, Ian McDermott, Ellen Quish, Preethi Radhakrishnan, and Allyson Sheffield, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

LIN 175: Information Literacy © 2022 by Steely Library Education & Outreach Services, Northern Kentucky University, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Science of Learning Concepts for Teachers (Project Illuminated) © 2020 by Marc Beardsley, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

University Success © 2016 by University of Saskatchewan, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.