FDA’s Role in Pharmaceuticals, Dietary Supplements and Foods

History of the FDA

The Food and Drug Administration or FDA is the oldest consumer protection agency within the US government. The FDA’s origin began in 1906 with the passage of the Pure Food and Drugs Act, a law that prohibited interstate commerce in adulterated and misbranded (i.e. containing additives that were not listed clearly and/or potentially hazardous) food and drugs.[1] However, the FDA didn’t officially become known as such until the 1930. In 1938, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) into law, increasing federal regulatory authority over drugs through implementation of a premarket review of safety and a ban on false therapeutic claims.[2] This law, although amended numerous times, remains as the foundation of the FDA’s regulation standards today.

The present mission of the FDA is to protect the public health by ensuring the safety, efficacy, and security of human and veterinary drugs, biological products, and medical devices; and by ensuring the safety of our nation’s food supply, cosmetics, and products that emit radiation.[3] While the FDA is responsible for all of the categories listed above, for the purpose of this book, the scope will be limited to drugs and food products.

| Year | Piece of Legislature | Purpose |

| 1906 | Pure Food and Drug Act | Banned foreign interstate traffic in adulterated or mislabeled food and drug products |

| 1938 | Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act | Gave the FDA authority to oversee the safety of food, drugs, medical devices, and cosmetics |

| 1958 | Food Additives Amendment | Amendment to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act that was created in response to concerns about the safety of food additives. This amendment established the classification of “generally recognized as safe” (GRAS). |

| 1966 | Fair Packaging and Labeling Act | Requires labels on consumer products to state:

|

| 1987 | Prescription Drug Marketing Act | Established legal safeguards for prescription drug marketing and sales to ensure the safety and effectiveness of drugs. |

| 1990 | Nutrition Labeling and Education Act | Gave the FDA authority to require nutritional labeling of most foods and ensure that nutrient content and health claims meet FDA regulations |

| 1994 | Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act | Defines and regulates dietary supplements; regulates for good manufacturing practices (GMP) |

| 2011 | FDA Food Safety Modernization Act | Set regulations to improve the safety of the food supply and prevent foodborne illness. |

FDA’s Role in Pharmaceuticals

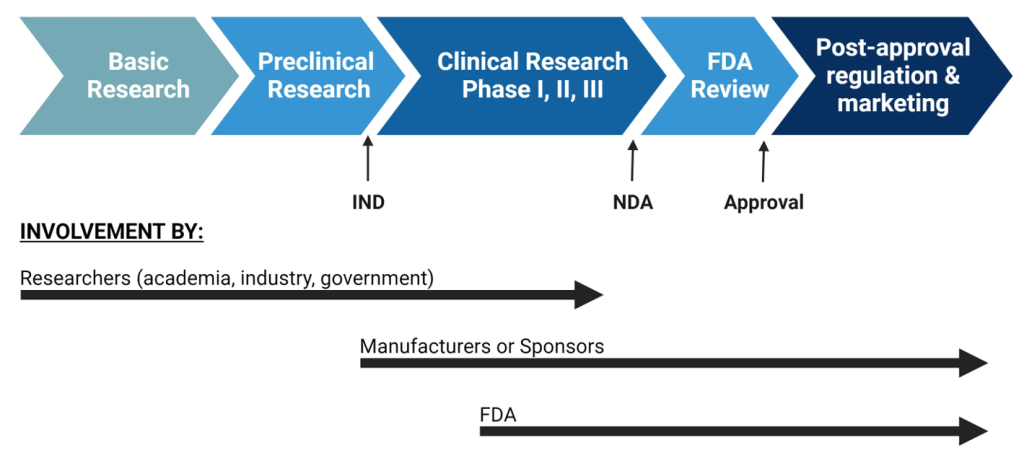

To market any prescription drug in the US, the manufacturer must first obtain FDA approval. To do this, the manufacturer must demonstrate the drug’s safety, efficacy, and effectiveness.[5] The FDA measures safety by 1) testing the toxicity of a drug to determine the optimal dose needed to achieve desired result or the highest tolerable dose and 2) identifying potential adverse effects of the use of the drug. Efficacy is determined based on how a drug performs over placebo or other intervention when tested in a tightly controlled situation, such as a clinical trial. Effectiveness examines how the drug works in a real-world situation and considers interactions with other medications the patient may be taking and other comorbidities that the patient may have that might alter how the drug acts.[6] These parameters are examined in Phase I, II, and III clinical trials. Prior to initiation of clinical development and clinical trials, the manufacturer must submit an “Investigational New Drug Application” (IND) which details information about proposed clinical study designs, animal test data that shows safety and efficacy, and qualifications of the lead investigators.[7]

| Phase | Objective | Length; Number of people |

| I | To determine safety and highest dose without adverse side effects. To identify acute side effects; to document metabolism and excretion pathways. About 70% of drugs pass this phase. | Several months to 1 year; 10-30 people |

| II | To test drug effectiveness, sometimes compared to different treatments. Randomized and typically double blinded clinical trials. About one-third of drugs successfully complete this phase. | About 2 years; up to several hundreds of people |

| III | Large-scale randomized and double-blind testing to determine whether the new drug works better than current drugs. Approximately 70-90% of drugs that reach this phase make it to market and obtain FDA approval. | Several years; hundreds to thousands of patients |

After clinical trials, the manufacturer has to submit a “New Drug Application” (NDA) to the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. The NDA contains information about clinical trial results as well as information about manufacturing processes and facilities that are utilized for drug production.[9] When reviewing an NDA, the FDA examines three main parameters:

- Evidence for the drug’s safety and effectiveness; whether benefits of use outweigh the risks

- Appropriate and complete proposed labeling information

- Manufacturing methods that maintain drug quality, and/or preserve its structure and purity

Once drugs are approved, the FDA remains responsible for managing and regulating them on the market. This is referred to as “post-approval regulation” and is overseen by the Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology (OSE).[10] Post-approval regulation involves monitoring safety and adverse outcomes, continuously reviewing relevant literature, and comparing similar drugs on the market to predict potential issues. Overall, the role of the FDA in drug regulation is to ensure the safety of human consumption through regulation of quality, manufacturing, and marketing.

Figure 4.1. Overview of drug development[11]

FDA’s Role in Foods

The FDA defines food as “articles used for food or drink for man or other animals, chewing gum, and articles used for components of any such article” (56). This is intentionally vague in order to allow the FDA to determine what exactly constitutes food and created standards at which to evaluate foods. Standards for commercially available food in the US are outlined in Chapter IV of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) which identified two main categories of food that violates these standards: “adulterated” and “misbranded” food.[12]

Adulterated food is defined as a food that “bears or contains any poisonous or deleterious substance which may be rendered injurious to health”. Foods may also be considered adulterated if they are manufactured in unsanitary conditions, produced from a diseased or improperly slaughtered animal, packaged in unsafe materials, or irradiated outside of guidelines set in place in the FD&C Act.[13] The FDA regulates this through inspections of manufacturing establishments, which may be unannounced. Results of inspections are used to generate an Establishment Inspection Report (EIR) that details any issues or problems noted.[14]

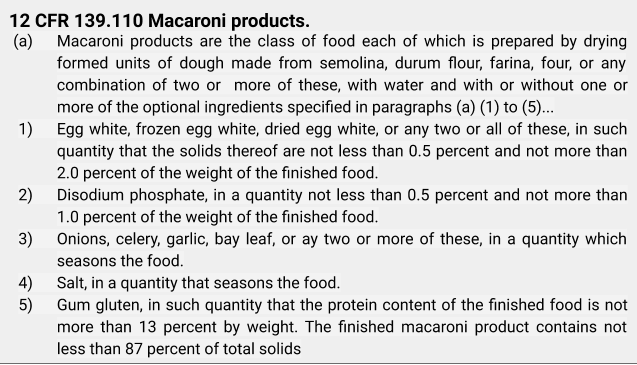

Misbranded food is considered as such if “its labeling is false or misleading in any particular way”. The FDA determines this through inspection of any containers/wrappers utilized for packaging as well as any pamphlet or booklet that may accompany an item. One example of how the FDA regulates branding is through setting standards of identity for foods.[15] This is a description that describes what exactly must be in a specific food for it to be labeled under a certain name, setting minimum and maximum requirements, optional ingredients, and prohibited ingredients. The FDA currently has over 300 identity standards in 20 categories of foods. An example of a typical standard of identity is in Figure 3.2.

The FDA does not monitor and regulate advertising of foods, as this regulation falls under the scope of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC).[16] Health claims on food labels are included within regulations enforced by the FTC. The FDA does not regulate meat, poultry, and certain egg products; regulation of these products falls under the scope of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

FDA’s Role in Dietary Supplements

Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 was enacted to define and regulate dietary supplements and also to regulate good manufacturing practices (GMP) of companies producing the supplements to ensure the safety of the public.[17]

The definition of a dietary supplement under the DSHEA is “a product (other than tobacco) intended to supplement the diet that bears or contains one or more of the following dietary ingredients: a vitamin, a mineral, an herb or other botanical, an amino acid, a dietary substance for use by man to supplement the diet by increasing the total dietary intake, or a concentrate, metabolite, constituent, extract, or any combination of the aforementioned ingredients.”[18]

Under the DSHEA, dietary supplements must also abide by labeling guidelines. To meet FDA standards, a dietary supplement label must include the following:[19]

- Statement of identity that contains the words “dietary supplement” or use the dietary ingredient to replace the word “dietary”.

- Net quantity of contents

- Supplement Facts panel (serving size, amount, percent daily value, of each ingredient)

- If contains a proprietary blend, net weight and listing of ingredients in descending order of weight

- The part of the plant used, if an herb or botanical

- Complete list of ingredients by common or usual names in descending order

- Safety information about the consequences that may result from use

- Disclaimer “This statement has not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease”

An important distinction to make with the FDA’s regulation of dietary supplements is that the FDA only regulates the manufacturing processes and labeling standards for the supplement. The FDA does not examine effectiveness, safety, and actual content of dietary supplements and only has a limited capacity to monitor adverse reactions from supplements. However, if there is ample proof that a supplement is dangerous or poses a “significant and unreasonable risk” the FDA may ban it.[20]

- Borchers AT, Hagie F, Keen CL, Gershwin ME. The history and contemporary challenges of the US Food and Drug Administration. Clin Ther. 2007;29(1):1-16. ↵

- Borchers AT, Hagie F, Keen CL, Gershwin ME. The history and contemporary challenges of the US Food and Drug Administration. Clin Ther. 2007;29(1):1-16. ↵

- Borchers AT, Hagie F, Keen CL, Gershwin ME. The history and contemporary challenges of the US Food and Drug Administration. Clin Ther. 2007;29(1):1-16. ↵

- Borchers AT, Hagie F, Keen CL, Gershwin ME. The history and contemporary challenges of the US Food and Drug Administration. Clin Ther. 2007;29(1):1-16. ↵

- Dabrowska A, Thaul, S. How the FDA Approves Drugs and Regulates Their Safety and Effectiveness. In: Service CR, editor. 2018. ↵

- Dabrowska A, Thaul, S. How the FDA Approves Drugs and Regulates Their Safety and Effectiveness. In: Service CR, editor. 2018. ↵

- Dabrowska A, Thaul, S. How the FDA Approves Drugs and Regulates Their Safety and Effectiveness. In: Service CR, editor. 2018. ↵

- Dabrowska A, Thaul, S. How the FDA Approves Drugs and Regulates Their Safety and Effectiveness. In: Service CR, editor. 2018. ↵

- Dabrowska A, Thaul, S. How the FDA Approves Drugs and Regulates Their Safety and Effectiveness. In: Service CR, editor. 2018. ↵

- Dabrowska A, Thaul, S. How the FDA Approves Drugs and Regulates Their Safety and Effectiveness. In: Service CR, editor. 2018. ↵

- Dabrowska A, Thaul, S. How the FDA Approves Drugs and Regulates Their Safety and Effectiveness. In: Service CR, editor. 2018. ↵

- Borchers AT, Hagie F, Keen CL, Gershwin ME. The history and contemporary challenges of the US Food and Drug Administration. Clin Ther. 2007;29(1):1-16. ↵

- Borchers AT, Hagie F, Keen CL, Gershwin ME. The history and contemporary challenges of the US Food and Drug Administration. Clin Ther. 2007;29(1):1-16. ↵

- Borchers AT, Hagie F, Keen CL, Gershwin ME. The history and contemporary challenges of the US Food and Drug Administration. Clin Ther. 2007;29(1):1-16. ↵

- Borchers AT, Hagie F, Keen CL, Gershwin ME. The history and contemporary challenges of the US Food and Drug Administration. Clin Ther. 2007;29(1):1-16. ↵

- Borchers AT, Hagie F, Keen CL, Gershwin ME. The history and contemporary challenges of the US Food and Drug Administration. Clin Ther. 2007;29(1):1-16. ↵

- Swann JP. The history of efforts to regulate dietary supplements in the USA. Drug Test Anal. 2016;8(3-4):271-82. ↵

- Swann JP. The history of efforts to regulate dietary supplements in the USA. Drug Test Anal. 2016;8(3-4):271-82. ↵

- Swann JP. The history of efforts to regulate dietary supplements in the USA. Drug Test Anal. 2016;8(3-4):271-82. ↵

- Swann JP. The history of efforts to regulate dietary supplements in the USA. Drug Test Anal. 2016;8(3-4):271-82. ↵

A law passed in 1906 that prohibited interstate commerce in adulterated and misbranded (i.e. containing additives that were not listed clearly and/or potentially hazardous) food and drugs

A law passed in 1938 that gave the FDA authority to oversee the safety of food, drugs, medical devices, and cosmetics

The maximum effect of which the drug is capable. A potent drug may have a low efficacy, and a highly efficacious drug may have a low potency.

A parameter that focuses on how a drug works in a real-world situation and considers interactions with other medications the patient may be taking and other comorbidities that the patient may have that might alter how the drug acts

A food that "bears or contains any poisonous or deleterious substance which may be rendered injurious to health"

A food where the "labeling is false or misleading in any particular way"

Defines and regulates dietary supplements and also regulates good manufacturing practices (GMP) of companies producing the supplements to ensure the safety of the public.

A product (other than tobacco) intended to supplement the diet that bears or contains one or more of the following dietary ingredients: a vitamin, a mineral, an herb or other botanical, an amino acid, a dietary substance for use by man to supplement the diet by increasing the total dietary intake, or a concentrate, metabolite, constituent, extract, or any combination of the aforementioned ingredients