9 Expanding Horizons: Medicare, Medicaid, and Beyond

Stephanie Saulnier

Section 9.1: Healthcare Reforms: Medicare and Medicaid

In 1926, Harry Hopkins, later involved with developing the New Deal legislation, wrote, “The fields of social work and public health are inseparable, and no artificial boundaries can separate them. Social work is interwoven in the whole fabric of the public health movement, and has directly influenced it at every point” (Ruth & Marshall, 2017, p. S236).

Concerns about public health and health care in the US dates all the way back to the colonial days. In 1798, the Act for the Relief of Sick and Disabled Seamen authorized marine hospitals to care for American merchant seamen focused on both treatment and the prevention of the spread of disease.

Figure 9.1: First Marine Hospital owned by the Federal Government

In the early 19th century, social workers in both the charity organization movement and the settlement house movement were involved in healthcare and public health, focusing on the “social side of illness.” Social workers served as case managers in local health departments working with vulnerable patients and families coping with unemployment and hospitalizations (Ruth & Marshall, 2017). The establishment of the Children’s Bureau in 1912, came out of advocacy by social workers focused on the protection and well-being of children.

The 1921 Maternity Health Act, also known as the Sheppard-Towner Act, was the first federal health care funding focused on prevention. The legislation addressed real concerns about infant and maternal mortality and established a precedent for the federal government’s role in health care for children. It expired in 1929 but was reauthorized as Title V of the Social Security Act.

Despite pushes as early as 1912 for federal or national health insurance, it wasn’t until 1946 with the passage of the Hill-Burton Act, that the federal government played a significant role in the access of healthcare to all Americans. Rural social workers were vocal about the lack of hospital care in rural areas, particularly in the South. The Hill-Burton Act provided federal funding to build rural hospitals. After this act, there was an opening for the federal government to move toward more involvement in the provision of healthcare for vulnerable populations.

During his presidency, Harry S. Truman advocated for a national health insurance plan, but fierce opposition warning against “socialized medicine” led him to abandon his vision for universal coverage. His focus shifted to Social Security beneficiaries as their numbers and needs continued to expand (Smith, 2023).

By 1960, it had become evident that private insurers were struggling to provide comprehensive, affordable health care to the rapidly growing population of older adults, reinforcing the urgency for a government-backed solution.

As the debate over a national health insurance program for the elderly intensified in 1960, Congress introduced the Kerr-Mills program, providing federal grants to states to support medical services for indigent elderly individuals. Federal officials in the Welfare Administration of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare saw an opportunity to expand this initiative, particularly to ensure access to health care for children on welfare—the largest group of welfare beneficiaries.

In 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson, with former President Truman looking on, signed the original Medicare program consisting of Part A, covering hospital insurance, and Part B, which provided medical insurance, known as “Original Medicare.” Over the years, Congress expanded the scope of Medicare, recognizing the evolving needs of the population. In 1972, eligibility widened to include individuals with disabilities, people suffering from end-stage renal disease. Additionally, new benefits were introduced, such as prescription drug coverage and a managed care option.

Medicaid, initially created to offer medical insurance to individuals receiving cash assistance, also evolved. Today, it extends vital healthcare services to a much broader group, including low-income families, pregnant women, individuals of all ages with disabilities, and those in need of long-term care.

Here is a great video about celebrating the 50th anniversary of Medicare.

Section 9.2: Disability Rights and the Americans with Disabilities Act

In 1990, the Americans with Disabilities Act finally established in federal law that people with disabilities have the same rights and opportunities as everyone else in areas like employment, public services, and accessibility. By expressly prohibiting discrimination and requiring reasonable accommodations, people with disabilities were ensured equal access to public spaces, transportation, and other essential aspects of daily life. This piece of legislation was the culmination of a very long history of advocacy for and by people with disabilities since the beginning of the country.

The Brown V. Board of Education Supreme Court victory started the Disability Rights Movement (DRM) legal conversation by ruling that separate facilities for any reason were a form of discrimination (Mayerson, 2017). From this ruling came the first real legislation based on equal access for people with disabilities – the Architectural Barriers Act of 1968 stipulated that separate facilities were not equal and that any facility built with or receiving federal funds had to be accessible to all. This movement is based on the principle that people with disabilities are entitled to the same civil rights, options, and control over choices in their lives as people without disabilities .

Two critical cases in the early 1970s – Pennsylvania Association for Retarded Children (“P.A.R.C”) v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and Mills v. Board of Education – addressed the issue of education for children with disabilities. At the time, millions of children with disabilities were refused enrollment in public schools, were inadequately served by public schools, or were sent to institutions. These lawsuits led to the 1975 Education of All Handicapped Children Act which guaranteed children with disabilities the right to public school education.

In both landmark cases, the Courts interpreted the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to give parents educational rights for their children, struck down local laws that excluded children with disabilities from public schools and established that children with disabilities have the right to a public education. This meant that no child could be denied a public education because of “mental, behavioral, physical or emotional handicaps or deficiencies.” Going even further, the Supreme Court ruled that schools could not use the excuse of cost or insufficient funding to deny children the right to a free, appropriate public education.

The enactment of Section 504 of the 1973 Rehabilitation Act. Section 504, banned discrimination on the basis of disability by recipients of federal funds, modelled after previous federal laws that banned race, ethnic origin and sex-based discrimination by federal fund recipients. Finally, excluding and segregating people based on disability status was viewed as discrimination. Previously, it had been assumed that the problems faced by people with disabilities, such as unemployment and lack of education, were inevitable consequences of the physical or mental limitations imposed by the disability itself. Enactment of Section 504 evidenced Congress’ recognition that the inferior social and economic status of people with disabilities was not a consequence of the disability itself, but instead was a result of societal barriers and prejudices. As with racial minorities and women, Congress recognized that legislation was necessary to eradicate discriminatory policies and practices.

In 1975, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), specifically addressed the right to a free, appropriate public education for all students, including those with severe disabilities. IDEA established “individualized education program” (IEP) and required education to be provided in the “least restrictive environment” possible. IDEA has been reauthorized several times since 1975 but advocates and parents still struggle to ensure that students with disabilities receive the services they need to be successful.

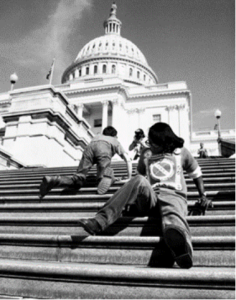

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) passed in 1990 in the face of fierce opposition from powerful lobbies worried about the impact of the cost on businesses. As the legislation was slowly making its way through the legislative process, disability advocates became more and more frustrated. Their frustration about a lack of concern about the daily struggles people with disabilities encountered culminated in a protest on the steps of the US Capitol where people with physical disabilities got out of their wheelchairs and walkers and crawled up the Capitol steps. This event has since become known as the “Capitol Crawl.” The message was heard and in July of that year, the act was signed by President George H.W. Bush (Mayerson, 2017).

Figure 9.2: ADA Protestors on the steps of the Capital

The fight for accessibility had just started through with the passage of the ADA. Businesses that were required to become accessible immediately took the fight to the US Supreme Court and the implementation of the law was slowly shaped through lawsuits and regulations at the federal and state levels.

One of the biggest lawsuits happened in 1999 and resulted in a major change to how states provided services for people with mental illness and cognitive disabilities. On June 22, 1999, the US Supreme Court held in Olmstead v. L.C. (Olmstead) that unjustified segregation (institutionalization) of persons with disabilities constitutes discrimination in violation of Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act. The Olmstead decision required that each state establish funding for people with disabilities to live and receive services in the community instead of large state-run institutions.

References:

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (2024, Sept. 10). History. https://www.cms.gov/about-cms/who-we-are/history.

Thomas, K.K. (2011). Deluxe Jim Crow : Civil Rights and American Health Policy, 1935-1954. University of Georgia Press.

Ruth, B. J., Marshall, J. W. (2017). A history of social work in public health. American Journal of Public Health 107(53). S236-S242. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304005

Kruse, K. E. (2011). Deluxe Jim Crow : Civil Rights and American Health Policy, 1935-1954. University of Georgia Press.

Smith K. (2023) A (brief) history of health policy in the United States. Delaware Journal of Public Health 9(5). 6-10. doi: 10.32481/djph.2023.12.003.

Berkowitz E. (2005). Medicare and Medicaid: the past as prologue. Health Care Finance Review 27(2), 11-23.

Mayerson, A. (2017). The history of the Americans with Disabilities Act. Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund (DREDF).https://dredf.org/the-history-of-the-americans-with-disabilities-act/

Scotch, R.K. (2009). “Nothing About Us Without Us”: Disability Rights in America, OAH Magazine of History 23(3), 17–22, https://doi.org/10.1093/maghis/23.3.17

Farrell, S. (2025) From the Archives: Promises and Pitfalls of the Disability Rights and Independent Living Movement Project. The Oral History Review (52)1,87-110, DOI: 10.1080/00940798.2025.2468517

Meldon, P. (2025). Disability History: The Disability Rights Movement. National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/articles/disabilityhistoryrightsmovement.htm