7 The War Years: Social Welfare During and After WWII

Brandon Edwards

Section 7.1: The G.I. Bill

Veterans lining up for a last day rush to get counseling on GI bill educational courses at the New York regional office Veterans Administration on July 25, 1951. Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, commonly known as the GI Bill, is one of the most significant and transformative pieces of social legislation in American history. From the perspectives of social work and social welfare, it represents a monumental, albeit flawed, investment in human capital that reshaped the economic and social landscape of the United States after World War II. The legacy of the Bill is marked by contrasts: while it served as a powerful engine of upward mobility for millions, it also entrenched and exacerbated existing racial and gender inequalities. This highlights the complexities involved in implementing social policy.

Averting a Crisis, Investing in a Future: The Genesis of the GI Bill

The GI Bill was created for two main reasons: shaped by past experiences and future concerns. Lawmakers and veterans’ organizations, especially the American Legion, were acutely aware of the social and economic chaos that followed World War I. The “Bonus Army March” of 1932, during which thousands of struggling veterans gathered in Washington D.C. to demand promised payments, left a profound impact on the nation (Zinn Education Project, n.d.). Policymakers were determined to avoid a repeat of that trauma. With over 16 million Americans serving in World War II, there were significant worries about mass unemployment and economic instability as veterans returned home. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and a bipartisan group in Congress viewed the GI Bill as a proactive measure to facilitate the reintegration of veterans into the workforce and prevent a relapse into the Great Depression (Sparrow, 2020). By framing the GI Bill in this manner, it is positioned within the tradition of social welfare aimed at promoting economic stability and preventing social unrest.

The Pillars of Opportunity: Key Provisions and Their Social Impact

The GI Bill was a comprehensive set of benefits aimed at helping veterans transition back to civilian life. Its three main pillars had significant implications for social welfare:

- Education and Vocational Training: The bill provided funding for tuition, fees, and a living stipend, enabling veterans to attend college or vocational school (Vergun, 2019). This was a groundbreaking expansion of access to higher education, which had previously been limited to the wealthy elite. The results were impressive: by 1947, veterans represented nearly half of all college admissions (American RadioWorks, 2015). This initiative is celebrated for creating a more educated and skilled workforce, which in turn contributed to post-war economic growth and innovation. From a social work perspective, this represents a significant investment in individual capacity building, empowering veterans to achieve greater self-sufficiency and upward mobility.

- Loan Guarantees for Homes, Businesses, and Farms: The GI Bill provided federally backed, low-interest loans with minimal down payments, making homeownership an achievable dream for a new generation of Americans (Centre for Public Impact, 2019). This initiative led to a construction boom and the rapid expansion of suburbs. The social implications were significant, as it contributed to the growth of the American middle class and promoted the ideal of the nuclear family living in a single-family home. Additionally, this effort addressed a fundamental need for stable housing, which is a key determinant of health and well-being.

- Unemployment Readjustment Allowances: To establish a safety net, the bill included up to 52 weeks of unemployment benefits, commonly known as the “52-20 Club,” which provided $20 per week (Centre for Public Impact, 2019). This provision served as an essential buffer, helping to prevent immediate poverty for veterans who were struggling to find work, and ensured a level of economic security during their transition.

The Great Failure (Discrimination and the Widening of the Racial Divide):

The GI Bill was originally designed as a comprehensive program to provide equal access to higher education, housing, and economic opportunities for all qualified veterans returning from World War II. However, its implementation revealed significant inequities, highlighting failures in the social justice and welfare systems in the United States (Heller School for Social Policy and Management, 2023). The management of the GI Bill was primarily entrusted to state and local authorities, especially the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). This decentralized approach inadvertently allowed systemic racism to persist, echoing the legacy of Jim Crow laws. As a result, many African American veterans faced major obstacles, including outright denial of benefits and strict restrictions that marginalized their access to resources intended to help them integrate back into civilian life. This unfortunate reality exposed the profound challenges these veterans encountered, emphasizing the ongoing issues of inequality and social injustice, even within a program designed to support their transition back into society (Heller School for Social Policy and Management, 2023).

Educational Segregation and Denial:

The promise of homeownership for Black veterans turned out to be largely empty. Banks often denied their mortgage applications, even when backed by federal guarantees (Lawrence, 2022). Suburbs, such as the well-known Levittowns, explicitly practiced racial exclusion through restrictive covenants, which prevented Black families from accessing the wealth-building opportunities of homeownership that white families enjoyed. This discriminatory application of the GI Bill had devastating and long-lasting effects. While it enabled a generation of white veterans and their families to enter the middle class, it simultaneously widened the racial wealth gap (Lawrence, 2022). The very policy that created unprecedented opportunities for some reinforced systemic barriers for others, highlighting a critical lesson for social work: seemingly neutral policies can have profoundly different impacts on different groups.

Housing Discrimination:

The promise of homeownership was largely a hollow one for Black veterans. Banks frequently denied them mortgages, even with the federal guarantee. The burgeoning suburbs, like the iconic Levittowns, openly practiced racial exclusion through restrictive covenants, preventing Black families from participating in the wealth-building opportunities of homeownership that their white counterparts enjoyed (Devitt, 2025). This discriminatory application of the GI Bill had devastating and lasting consequences. While it propelled a generation of white veterans and their families into the middle class, it actively widened the racial wealth gap. The very policy that created unprecedented opportunity for some simultaneously reinforced systemic barriers for others, a critical lesson for social work in understanding how seemingly neutral policies can have profoundly disparate impacts (Devitt, 2025). Similarly, while women veterans were eligible for benefits, the program was largely designed with male veterans in mind. Social and institutional barriers often prevented women from taking full advantage of the educational and housing provisions, reinforcing traditional gender roles of the era.

The Evolution and Enduring Legacy of the GI Bill:

The original GI Bill ended in 1956, but its lasting impact is still felt today. Later versions, such as the Montgomery GI Bill and the Post-9/11 GI Bill, have continued the tradition of providing educational benefits to veterans. These iterations have addressed the inequities of the original by being administered at the federal level, which reduces the potential for localized discrimination (O’Brien, 2021). The Post 9/11 GI Bill, in particular, stands out as one of the most generous educational benefit programs since the original. It has also expanded benefits by allowing transferability to spouses and children, acknowledging the sacrifices made by military families (O’Brien, 2021). From a social welfare perspective, this represents a more holistic and family-centered approach to supporting service members.

The role of social workers within the VA has been crucial in implementing and evolving these benefits. Following World War II, social workers played a crucial role in helping veterans navigate the complexities of the VA system, offering counseling, and addressing the challenges of readjustment. Today, VA social workers continue to be at the forefront of meeting the multifaceted needs of veterans, including mental health and substance abuse issues, housing insecurity, and employment challenges. They are instrumental in connecting veterans with their earned benefits, including the GI Bill, and advocating for a more equitable and accessible benefits system.

The GI Bill remains a landmark in the history of American social welfare, demonstrating the profound effect that large-scale government investment can have on social mobility and economic prosperity. However, its history also serves as a cautionary tale. It highlights the critical importance of equitable implementation and how social policy can be undermined by systemic discrimination. For the field of social work, the GI Bill’s dual legacy serves as a potent reminder that pursuing social justice requires not only the creation of universal programs but also a steadfast commitment to dismantling the structural barriers that prevent these programs from benefiting all members of society equally.

Section 7.2: Post-War Social Welfare Policies

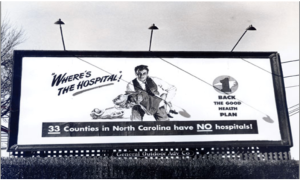

Figure 7.1: A billboard supporting the passage of the Hill-Burton Act of 1946

The period following World War II in the United States was marked by remarkable economic growth and social transformation. It saw a significant expansion of the American welfare state and substantial investments in the well-being of the population, which contributed to the rise of the white middle class. However, this progress was built on a foundation of exclusion, leading to what has been described as the “submerged” or “hidden” welfare state (Trattner, 2018). This system systematically overlooked and discriminated against African Americans and other minority groups, perpetuating inequality for generations. The political climate of the era was defined by a desire for stability, national unity in the context of the Cold War, and a strong belief in American exceptionalism. President Harry S. Truman’s “Fair Deal” sought to build upon and expand the legacy of Roosevelt’s New Deal. However, this progressive push often clashed with a conservative Congress and the entrenched realities of Jim Crow segregation (Trattner, 2018).

Pillars of a Segregated Welfare State

-

- The Hill-Burton Act of 1946 (Hospital Survey and Construction Act): The Hill-Burton Act was significant as a public health initiative aimed at addressing the severe shortage of medical facilities in the United States (Yim, 2025). It provided federal grants to states for the construction of hospitals, effectively modernizing the nation’s hospital infrastructure, especially in rural and underserved areas. From a social welfare perspective, this demonstrated a strong federal commitment to improving public health and access to care. However, the act had a critical flaw: it included a concession to racism. To gain the support of Southern Democrats, the legislation contained a “separate but equal” clause, which allowed for the establishment of segregated health facilities (Yim, 2025). This provision effectively used federal funds to institutionalize racial discrimination in healthcare. For social work, which is based on the principle of equitable access, the Hill-Burton Act serves as a stark example of how social policy can reinforce systemic inequality, leading to enduring health disparities. It wasn’t until the landmark 1963 court case Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital that this provision was successfully challenged, setting the stage for the desegregation of hospitals under the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Thomas, 2006).

- The National Mental Health Act of 1946: The horrors of war, especially the high rates of “combat fatigue”—now recognized as PTSD—among soldiers, brought mental health issues to the forefront of national awareness (Pitt, 2024). The National Mental Health Act was a pivotal moment, as it established the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and marked the beginning of a significant federal role in mental health research, training, and service provision. From a social welfare perspective, this act was transformative. It provided substantial funding for the training of mental health professionals, including psychiatric social workers, whose numbers grew significantly as a result (Pitt, 2024). It encouraged a shift away from purely institutional care towards the idea of community-based mental health services. This legislation elevated the role of social work in the mental health field and solidified the profession’s expertise in clinical settings within the emerging mental health system. However, access to these new services was often limited for minority populations, who faced both institutional barriers and cultural biases in treatment.

- The Social Security Amendments of 1950: The 1950 amendments significantly expanded the American social safety net, often overshadowed by the original 1935 act. These amendments included approximately 10 million additional workers—many of whom were self-employed, as well as domestic and farm workers—under the Old Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) program (Johnson, 2021). They nearly doubled the average benefit levels, transforming Social Security from a limited program into a nearly universal system of social insurance for seniors. In terms of social welfare, this expansion was a significant success, providing a stronger defense against poverty in old age. The amendments also made an important change to Aid to Dependent Children (ADC) by recognizing the caretaker—who was typically the mother—as a recipient of federal matching funds (Johnson, 2021). This acknowledged the needs of the entire family unit. However, the initial exclusions of agricultural and domestic workers in the 1935 Act disproportionately affected African Americans and Latinos (Grossbard-Shechtman, 2003). While the 1950 amendments were a corrective measure, they could not undo the decade and a half during which these minority workers were unable to accumulate Social Security credits, resulting in a disadvantage that compounded over time (Aid to dependent children, 1961).

The post-war era was not merely a straightforward era of progress. It represented a period of extensive, state-sponsored social investment that fundamentally transformed American society, demonstrating how social policy can create opportunities and improve living standards. However, from a social welfare perspective, its legacy is closely tied to its failures in promoting equity. The policies of this period actively constructed a segregated welfare state, providing a pathway to the middle class for millions of white Americans while systematically blocking access for their Black counterparts—a legacy of inequality that the social upheavals of the 1960s would directly confront.

References

Aid to dependent children. (1961). CQ almanac 1961 (17th ed.). http://library.cqpress.com/cqalmanac/cqal61-1373151

American RadioWorks. (2015). The history of the GI Bill. APM Reports. https://www.apmreports.org/episode/2015/09/03/the-history-of-the-gi-bill

Centre for Public Impact. (2016). The US GI Bill: The new deal for veterans. https://centreforpublicimpact.org/public-impact-fundamentals/the-us-gi-bill-the-new-deal-for-veterans/

Devitt, J. (2025). The legacy of Levittowns. New York University. https://www.nyu.edu/about/news-publications/news/2025/march/the-legacy-of-levittowns.html

Grossbard-Shechtman, S. (2003). Marriage and the economy: Theory and evidence from Advanced Industrial Societies. Cambridge University Press.

Heller School for Social Policy and Management. (2023). Not all WWII veterans benefited equally from the GI Bill. https://heller.brandeis.edu/news/items/releases/2023/impact-report-gi-bill.html

Lawrence, Q. (2022). Black vets were excluded from GI Bill benefits. A bill in Congress aims to fix that. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2022/10/18/1129735948/black-vets-were-excluded-from-gi-bill-benefits-a-bill-in-congress-aims-to-fix-th

Pitt, J. (2024). Mobilizing for the mind: Veteran activism and the National Mental Health Act of 1946. Journal of Policy History, 36(2), 215–241. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0898030623000374

Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, Pub. L. No. 78-346, 58 Stat. 284 (1944).Sparrow, P. (2020). FDR and the GI Bill. FDR Library. https://fdr.blogs.archives.gov/2020/11/10/fdr-gi-bill/

Thomas, K. K. (2006). The hill-burton act and civil rights: Expanding hospital care for black southerners, 1939-1960. The Journal of Southern History, 72(4), 823. https://doi.org/10.2307/27649234

Trattner, W. I. (2018). From poor law to welfare state (6th ed.). Simon & Schuster, Incorporated.

Vergun, D. (2019). 75 years of the GI Bill: How transformative it’s been. U.S. Department of Defense. https://www.defense.gov/News/Feature-Stories/story/Article/1727086/75-years-of-the-gi-bill-how-transformative-its-been/

Yim, S. (2025). The Hill-Burton Act: Instituting Healthcare Infrastructure and Perpetuating Structural Racism. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/cxh6q_v1

Zinn Education Project. (n.d.). July 28, 1932: U.S. Army attacks Bonus Army marchers. https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/bonus-army-attacked/