Chapter 5: Mindset and Motivation

It’s never too late to learn something new

To reach your academic goals and pass your expectations, finding and maintaining motivation and engagement in school is an important first step to achievement and success. This section can help give ideas on how to find and maintain motivation to engage in the things you want to do.

Learning Objectives

This chapter will:

- Identify what a fixed mindset is and what a growth mindset is

- Explore motivation and engagement

- Provide strategies to stay motivated and engaged

Fixed mindset and Growth Mindset

One of the main purposes of college is to develop our minds and become more complex, flexible thinkers. Our brains can be shaped, developed, and changed throughout our entire lifespans. The extent to which we can develop our minds depends on our beliefs about how our minds work. We all set our minds to believe certain things, and our beliefs help or hinder us as we move through life. Our beliefs and our ways of thinking develop into habits of mind. Numerous psychologists have researched this topic. One of the best-known researchers in this area is Dr. Carol Dweck, who has studied these habits of mind extensively, and explored the effects of fixed and growth mindsets on individuals’ learning.

When people have a fixed mindset, they generally believe they are born with a certain amount of talent and intelligence that can’t be changed or can only take them so far in life. Students with a fixed mindset might say, “I just can’t do it!”; “I’m not good at math”; “I guess college isn’t for me!” or “I’m not smart enough” because they compare themselves to others or feel that effort is futile. These students tend to focus only on results, so a low score on a test may indicate to them what they already believed: they’re not smart enough to succeed.

When you have a growth mindset, you tend to think that your intelligence can change through experience and effort, and that you can do anything you set your mind to doing. Students with a growth mindset might say, “I made a mistake, but I can learn from that and do better next time,” or “If I give myself more time and utilize resources, I can write a better essay next time.” This is because they believe that putting in effort and practice will lead to positive results and increased competence. Students with a growth mindset tend to focus on the processes of learning in each discipline, so a low paper score may indicate to them that they need to review the rubric and identify which stages of the writing process they could spend more time on to do better on the next assignment. Take a moment to view the video, “Growing Your Mind,” to understand what determines your intelligence. This video explains how your intelligence can improve over time. To improve your intelligence, you must have grit, perseverance, and a growth mindset.

| Fixed Mindset Personality

Attitude & Approaches |

Key Elements of Learning | Growth Mindset Personality

Attitudes & Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Everyone is born with certain skills and aptitudes. | Beliefs about human potential | With effective strategies and time, people can improve their skills and aptitudes. |

| Believe abilities and knowledge that come easily indicate natural talent, and that if something isn’t easy, it cannot be learned. | Effort and Difficulty | Value the effort itself as a ket element of gaining knowledge and mastery. |

| Generally avoid challenger and see obstacles as signs they are in the wrong direction. | Challenges and Obstacles | Seek out new challenges and see obstacles as problems to solve and ways to grow. |

| Hides or makes excuses for mistakes; becomes discouraged and frustrated by failure. | Mistakes and Failures | Takes ownership of mistakes and understands that failure often leads to learning and long-term success. |

| Rejects negative feedback and can become defensive; likely focuses on positive feedback. | Feedback, Criticism, and Suggestions | Appreciates the perspectives of others and welcomes candid feedback. |

| Success is limited to a few specific areas along a firmly defined pathway. | Outlook on the Future | Success is possible in many areas, once individuals create their own learning pathways. |

Figure 5.1: Fixed Mindset vs. Growth Mindset table

Factors of Motivation and Engagement

The properties of motivation and engagement are very complex as there are so many intertwined factors that can influence them. A problem many students face is determining which factor is causing them to be unmotivated or not engaged in school.

To help you identify the factors that are unmotivating and not engaging, fill out the interactive materials below. If you want more information about each factor and ways you can improve your motivation and engagement, you can interact with Figure X.

To find more information about each factor and ways you can improve your motivation and engagement, click any of the purple ‘i’s on the graphic below.

Motivation and Engagement: A Relationship

Motivation is the reason you are doing the assignment and engagement affects the quality of your input in the assignment. Both are important in success. They are independent of each other but together could make a world of difference and even make studying easier.

An Analogy: Pre-requisite classes

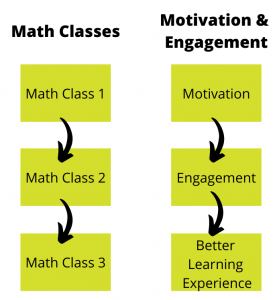

Figure 5.2: Performance in the prerequisite class can influence performance in future classes unless the quality of the input changes

With pre-requisite classes, you must complete the beginner class before continuing in studying the more challenging topics. In this case, Math 1 must be completed prior to Math 2. If the first course is completed with a lack of understanding of the topic, the second course will become harder unless the time, energy and care inputs are increased. However, if you pass Mass Class 1 with a high understanding of the concepts, Math Class 2 will be easier unless you begin to slack off and reduce your time, energy and care inputs.

Similarly, you must have the motivation to begin the learning activities before you can be engaged in them. Just as each math class is a separate, independent course, motivation and engagement are separate, independent, properties.

Some Examples of the Relationship between Motivation and Engagement

- You can be highly motivated, but it may not transition into high engagement. You can be highly motivated to find the quickest and easiest path to pass the assignment. In this example, you limit your time, energy, and care to only meet the requirements of the assignment and then move on to something more enjoyable.

- You can be highly engaged in the study assignment, but it may not mean you are highly motivated. In this example, you have decided to begin the study assignment so you might as well do a respectable job.

- You can be highly motivated and highly engaged. In this example, you find the study assignment you are doing the best thing in the world.

- You can have low motivation and low engagement. In this example you find the study assignment is the worst thing in the world.

Student Spotlight

Student Spotlight

“EKU felt like home when I toured. I wanted the full college experience—making memories and meeting new friends—but I also knew I wanted to be the first in my family to graduate and walk across that stage. Take full advantage of your time in college—it’s an amazing experience, and it goes by fast!”

-Lilly Morris,

Broadcasting and Electronic Media,

Class of 2026

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation

As we talked about briefly in Chapter 3: Metacognition, what type of mindset you have, and how you learn, depends on your motivation and how you maintain your motivation for learning. While there are many different learning styles, we can distinguish two major approaches to learning. One type of learner needs an outside stimulus to motivate their learning, or is extrinsically motivated. Extrinsic motivation is defined as a desire to engage in behavior for external reasons (Riley, 2016). This type of learner motivation is aimed at performance-based goals. Learners driven by extrinsic motivation focus on grades and rewards.

Intrinsic motivation, on the other hand, is driven by the learner’s own inner experience of reward and satisfaction that comes with the process of learning, without outside rewards. When intrinsically motivated, learners tend to focus more on the satisfaction they gain through the process of learning. Instead of learning for the grade or recognition, students begin to learn because they want to (Riley, 2016), which often leads to more in-depth learning. Intrinsic learning-based goals develop from curiosity, a belief that one can learn, determination and a willingness to overcome challenges to learning.

Carol Dweck identifies learners that have performance-based goals and learning-based goals, as having Fixed Mindsets and Growth Mindsets, respectively. Watch this video to learn more about how to develop a growth mindset from Carol Dweck.

Grit

Grit is a concept developed by the psychologist Angela Duckworth, who studied children and adult learners to discover that intelligence or talent did not necessarily determine success at learning a task. The concept of grit has been praised and criticized, and it’s important to understand it to tease out its limitations and possible areas of usefulness.

Studying individuals in various environments (including school and the workplace), Duckworth’s (2016) initial findings showed that neither overall intelligence nor other factors like “good looks” were the most significant predictors of individual success. Instead, she found that grit – “passion and perseverance for very long term goals” – was the most decisive factor in determining success. Critics have pointed out that Duckworth ignores significant predictors of success that are outside a person’s control, such as a family’s zip code or income level.

Characteristics of Grit

Courage: Gritty people are not afraid of failure. They welcome failure as part of the growth process. They brush themselves off and try again using what they learned from the experience of failure. Many people freeze up because they fear failure. Gritty people live by the words of Eleanor Roosevelt: “Do something that scares you everyday.”

Conscientiousness: Gritty people are meticulous while also achievement-oriented. They strive to do the best they possibly can and are tenacious. Gritty people do not complete just the minimum requirements of any task, they put their all into what they do and deliberately make the best effort possible at all times.

Commitment and focus on long-term goals: Gritty people find value and meaning in the effort that it takes to reach a long-term goal. They zone in on their goals and have the stamina to reach them.

Resiliency: Gritty people bounce back from setbacks and continue to bounce back until they have reached their goals. They are hardy and do not easily give up.

Focus on excellence: Gritty people focus on achieving excellence, not perfection. The former is a state of mind in which you continuously strive and grow to be the best that you can be. The latter is an unachievable status where better is never enough.

Do you feel like the story of grit does not capture the full picture? You’re not alone. Many academics and others have critiqued the usefulness of centering the concept of grit in our stories of growth. Have you ever heard the phrase, “pull yourself up by your bootstraps?” It suggests that all you need to succeed is to lift yourself up, fully under your own volition. It ignores that the people, systems, and environments around you can have profound effects on your ability to accomplish empowerment.

One concept that helps illustrate this critique of grit is another idea in the field of psychology, “learned helplessness.” It sounds like a concept used to belittle a person, but it’s actually a natural response to unpleasant stimuli that are beyond a person’s control. In the many types of experiments used to investigate the concept, animals were given unpleasant stimuli that one group had the ability to stop, and the other group was unable to stop or control. The second group learned to give up, because they were not able to stop painful events from affecting them. This is where the concept of “learned helplessness” originates. When a person experiences a series of negative factors beyond their control, it’s a common and intuitive response to develop learned helplessness. Some say the concept of grit fails to capture this nuance.

Growth Mindset, Failing, and Grit

Something you may have noticed is that a growth mindset would tend to give a learner grit and persistence. If you had learning as your major goal, you would normally keep trying to attain that goal even if it took you multiple attempts. Not only that, but if you learned a little bit more with each try, you would see each attempt as a success, even if you had not achieved complete mastery of whatever it was you were working to learn. People who believe their abilities can change through learning (growth vs. a fixed mindset) readily accept learning challenges and persist despite early failures.

Your motivation, ambition, hard work, and persistence helped you to acquire your skills. In other words, you have grit, shown perseverance, and have a growth mindset when it comes to the skills you identified. You will discover that you can also have grit, perseverance, and a growth mindset for most of the new skills you will be challenged to learn at college, by applying the same methods and strategies you used to gain your current skills.

College is the perfect place to build your intrinsic motivations for learning and developing your growth mindset, to persevere, and show your grit. College is where you have the most autonomy over your learning; you decide how you will progress. Most assignments require you to include your insights and ideas and independent thoughts. You will be encouraged and given many opportunities to network and be a part of the community of learners at college to build an environment in which you feel supported and safe to learn. In college there are also many resources at your disposal to help you accomplish your goals.

Overcoming Interpersonal Difficulties and Resolving Conflicts

Despite having the right motivation and mindset, there are still obstacles that create distractions as we move towards our goals. Sometimes the distractions stem from conflict. Conflicts among people who are interacting are natural. People have many differences in opinions, ideas, emotions, and behaviors, and these differences sometimes cause conflicts. Here are just a few examples of conflicts that may occur among college students:

- Your roommate is playing loud music in your room, and you need some quiet to study for a test.

- You want to have a nice dinner out, but your spouse wants to save the money to buy new furniture.

- Your instructor gave you a C on a paper because it lacks some of the required elements, but you feel it deserves a better grade because you think it accomplished more important goals.

- Others at your Greek house want to invite only members of other fraternities and sororities to an upcoming party, but you want to open up the guest list to include a wider range of students.

Rather than viewing disagreements as roadblocks or battles to be won, a growth mindset approaches conflict as an opportunity for learning, understanding, and strengthening relationships. Two things are necessary for conflict resolution that does not leave one or more of the people involved feeling negative about the outcome: attitude and communication.

A conflict cannot be resolved satisfactorily unless all people involved have the right attitude:

Respect the perspectives and behaviors of others. Accept that people are not all alike and learn to celebrate your differences. Most situations do not involve a single right or wrong answer.

Be open minded. Just because at first you are sure that you are right, do not close the door to other possibilities. Look at the other’s point of view. Be open to change—even when that means accepting constructive criticism.

Calm down. You can’t work together to resolve a conflict while you’re still feeling strong emotions. Agree with the other to wait until you’re both able to discuss it without strong emotions.

Recognize the value of compromise. Even if you disagree after calmly talking over an issue, accept that as a human reality and understand that a compromise may be necessary in order to get along with others.

With the right attitude, you can then work together to resolve the issue. This process depends on good communication:

Listen. Don’t simply argue for your position, but listen carefully to what the other says. Pay attention to their body language as you try to understand their point of view and ask questions to ensure that you do. Paraphrase what you think you hear to give the other a chance to correct any misunderstanding.

Use “I statements” rather than “you statements.” Explain your point of view about the situation in a way that does not put the other person on the defensive and evoke emotions that make resolution more difficult. Don’t say, “You’re always playing loud music when I’m trying to study.” Instead, say, “I have difficulty studying when you play loud music, and that makes me frustrated and irritable.” Don’t blame the other for the problem—that would just get emotions flowing again.

Brainstorm together to find a solution that satisfies both of you. Some compromise is typically needed, but that is usually not difficult to reach when you’re calm and have the right attitude about working together on a solution. In some cases, you may simply have to accept a result that you still do not agree with, simply in order to move on.

In most cases, when the people involved have a good attitude and are open to compromise, conflicts can be resolved successfully. Yet sometimes there seems to be no resolution. Sometimes the other person may simply be difficult and refuse to even try to work out a solution. Regrettably, not everyone on or off campus is mature enough to be open to other perspectives. With some interpersonal conflicts, you may simply have to decide not to see that person anymore or find other ways to avoid the conflict in the future. But remember, most conflicts can be solved among adults, and it’s seldom a good solution to run away from a problem that will continue to surface and keep you from being happy with your life.

Putting it All Together

In this section we discussed mindset, motivation, and engagement. You learned that intrinsic motivation is how you can develop your growth mindset and the key factors to intrinsic motivation are competency, autonomy, and relatedness.

So, remind yourself, how do YOU develop a growth mindset for everything you want to learn? You must see the need to learn, want to learn the skill, or create a reason to learn the skill. Determine your intrinsic motivation. Then YOU must sustain your motivation by:

Feeling competent: You must genuinely feel you can learn the skill. Reflect on your past success and integrate those strategies used to apply to the new skill. You have to be willing to put in the time and effort to improve your learning and be willing to humble yourself when you do not get it correct immediately so you don’t give up. You have to accept that failure is part of the learning process.

Having autonomy: You must have choices of how you learn to experience learning on your own terms. You have to look for options for how you complete tasks and accomplish goals.

Feeling relatedness: You must feel connected with your learning environment, instructors, professors, classmates, and other resources to help you develop your learning. You need to be a self-advocate and ask questions, take initiative to form study groups, seek resources that you need, ask for clarification when you need it, and offer assistance when you can.

Summary

- During your first semester, try to refocus your approach on a growth mindset rather than a fixed one.

- Motivation and engagement need to have a good relationship to help you gain knowledge while in college.

- Extrinsic motivation is a desire to engage in behavior for external reasons.

- Intrinsic motivation is driven by the learner’s own inner experience of reward and satisfaction that comes with the process of learning.

- Characteristics of Grit are: Courage, Conscientiousness, Commitment and focus on long-term goals, Resiliency, and Focus on excellence.

- Conflict resolution comes when all parties involved have the right attitude.

- Good communication includes listening, using “I” statements, and brainstorming a solution together.

References

Duckworth, A. (2016). Grit: The power of passion and perseverance. Scribner.

Riley, G., & English, R. M. (2016). The role of self-determination theory and cognitive evaluation theory in home education. Cogent Education, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2016.1163651

Attributions and Licenses

Parts of this chapter are adapted from the following sources:

College Success © 2024 by Tacoma Community College, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

First Year Seminar © 2022 by Kristina Graham, Rena Grossman, Emma Handte, Christine Marks, Ian McDermott, Ellen Quish, Preethi Radhakrishnan, and Allyson Sheffield, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Liberated Learners © 2022 by Terry Greene et al., licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.